Turning It Up: Volume As a Production Tool

How Glass Animals help us decompress (and I don't mean morning meditation).

Last year, my company bought a bluetooth speaker for the office.

I work in a small space with two (sometimes three) other people. If nobody’s in a meeting and we’re all just doing our thing, we’ll sometimes put that speaker to use. We’ll throw on lofi beats, or background jazz, or some other non-offensive, easy-listening background music to soothe our ears from the clacking of keyboards and squashing of bugs.

It’s relaxing, and pleasant, and not at all jarring or distracting.

That is, of course, until the day that I was asked to select the music.

Here are some things you should know about me:

I majored in music in college.

I like to listen to music while I work.

I like to listen to any music when I work; it can be quiet, it can be loud, it can be instrumental, it can be verbose.

So yeah. One day, I was asked to select the music.

This is it, I thought. They know that I’m a music major. They’re expecting something music major-y.

But wait, I thought more. Maybe the kind of music I like to work to isn’t the same kind of music they like to work to.

I ran through my options. There were safe choices, of course. Chet Baker for some tasteful jazz, or Debussy for some pleasing piano music, or even Mozart for some stalwart classical.

No, no, no. They’re all too easy…too predictable.

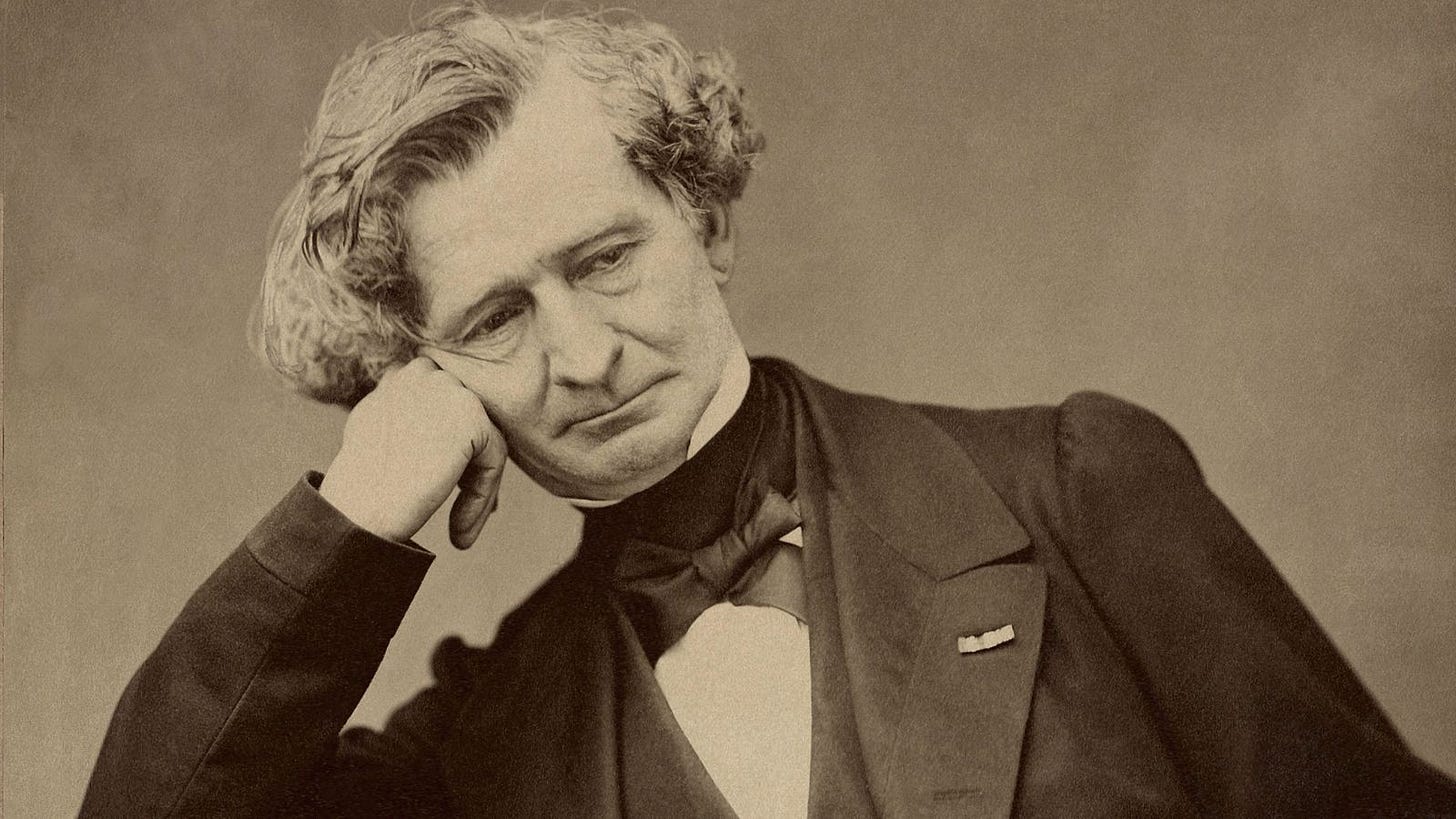

Then I recalled an assignment I had done in school that had me scrutinize the score of Hector Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique, hunting for entrances of the main theme (or, to utilize my education, the idée fixe). Despite being written in the 1800s, the piece felt contemporary and cinematic. But more importantly than that, I remembered it being a genuinely pleasant listen1.

Perfect.

It would have worked, too, if it weren’t for those meddling dynamics.

The piece started out quiet. A little too quiet. In fact, we couldn’t really hear anything for the first minute or so.

Naturally, we turned up the volume to compensate.

But then, the music got loud. A little too loud.

We quickly turned the speaker back down.

You’ll never guess what happened next!

It became a vicious cycle of volume adjustments, one which we endured for about two minutes before I admitted defeat and suggested we pivot to the scores of Michael Giacchino (Up, The Batman, Lost, and many more).

But what went wrong with Berlioz?

I’m glad you asked! For demonstration purposes, I have downloaded an mp3 of a performance of Symphonie Fantastique for you. Here is the waveform of that recording:

A quick breakdown of what we’re looking at:

We have two lines charting the volume (measured in decibels) of the performance

There are two lines because this recording is in stereo, which means that, if you were wearing earbuds, you would hear the top line in your left ear and bottom line in your right ear.

You can see that each line oscillates around some central axis. Here’s the key point: The further away the line travels from that central axis, the louder the song is at that moment.

So, by skimming the above image, you can get a sense of what I’m talking about. Berlioz veers from quiet to loud and vice versa with no regard for small office speakers.

To be clear, he isn’t alone in this; crescendos (getting louder) and diminuendos (getting quieter) are staples of classical music. Hardly anyone would write a piece with only one dynamic, because the result would be music that is boring and flat. Not to mention that the players themselves would probably get bored performing, and the best way to get your piece played (and therefore make money) is to make your piece fun to play.

But I’ve digressed; the point is that composers used to change dynamics all the time.

But why’d you say ‘used to’?

Because radio companies in the 1930s couldn’t deal with the dramatic shifts in volume. And so, rather than allow such rambunctious music to ruin their broadcast, they invented compression2.

Compression is turning down the loud parts of a song and turning up the quiet parts. It’s squeezing everything into a manageable volume range.

And today, it’s everywhere.

As an experiment, I downloaded the waveforms of Spotify’s top two songs in the US: Kendrick Lamar’s “Not Like Us” (link) and Sabrina Carpenter’s “Please Please Please” (link).

These represent two different genres of music with totally different different production styles. And yet, when we look at their waveforms, they look awfully similar. That’s because both songs slapped a pair of Copper Fits on the final mix, squeezing the track into a suitable range of decibels for easy listening.

But is compression bad?

No, compression isn’t bad. Standardizing the volume of a song is inherently necessary; that’s why it was invented in the first place. And besides the practical reasons (like not breaking radios), it’s kind of annoying to have to constantly turn a song up or down. Just ask my manager.

Plus, even though most songs are compressed, producers have grown adept at maintaining depth and dynamism in the mix.

Here’s the waveform for Imagine Dragons’ “Radioactive,” a song with notable dynamic changes. The choruses feel big, and they only get bigger as the song develops.

And yet, when we look at the volume…

We get the quiet opening, sure, but after that everything’s about the same volume. What changes, then, is the instrumentation, and the layering, and the mix itself. Producers have mastered the ability to make a big sound without making you turn down your speakers.

But isn’t volume a tool and, like any other production technique, should be used when appropriate for dramatic and/or narrative effect? And aren’t the producers leaving some potential on the table when they compress everything into a manageable but limited sonic range?

Yup.

Just ask Glass Animals3.

Exhibit A: “Heat Waves”

Listen here.

On more than one occasion I have carelessly turned up the volume at the start of this song, only to blow out my eardrums within the next five seconds:

This one’s similar to the “Radioactive” waveform, but much more heightened: the intro is way quieter relative to the rest of the song.

That’s because Glass Animals chose to start “Heat Waves” with the original demo that the lead singer recorded on his own when he first wrote the song. It’s not processed, and so it’s way quieter than the rest of the song.

If you scan the rest of the “Heat Waves” waveform, you’ll notice that it looks slightly different from the other songs we’ve looked at so far. Although you can tell the song is compressed, there’s definitely more variation in the volume level (particularly around the bridge) than we’ve seen in the previous songs.

Exhibit B: “The Other Side of Paradise”

Listen here.

Listen to this one and try to follow along on the waveform. Do you notice anything unique?

The choruses are louder than the verses.

I know this doesn’t seem like it should be a big deal; we learned in this newsletter about second verses that choruses are usually bigger and more filled-out than the rest of the song. So shouldn’t they be louder?

Nope! We’ve just looked at multiple songs with choruses that seem louder than the verses, but aren’t actually4. Producers will add more instruments, reverb, and energy to the chorus, but generally the volume level will stay about the same.

Glass Animals, on the other hand, actually go for it.

In the above waveform, you’ll find that the only time the volume is maxed out is during a chorus. The verses are quieter, and the bridge takes things really low before building back up to the chorus.

But if you think that build is good…

Exhibit C: “It’s All So Incredibly Loud”

Listen here.

Needless to say, a lot of songs grow over their runtime. What’s unique here isn’t so much the build itself as the degree of the build—the difference between the start and the finish in terms of raw decibels.

And that makes sense, because this song is called “It’s All So Incredibly Loud” and, if you start the song at a reasonable volume, you can’t help but agree with the title by the end.

Here’s the thing.

I guarantee you that Glass Animals compress all of their songs. Compression is ubiquitous at this point, and an untreated song stands out to the listener (even if they’re not sure what exactly sounds wrong).

The interesting and unique thing about Glass Animals is the way they allow their songs to vary in volume, sometimes extremely so, for dramatic effect. The ability to make something louder or quiet is perhaps the most basic element of music composition and production. Centuries ago, it was one of the only tools that composers like Berlioz had to affect the “mix” of their pieces. And today, it seems like one of the only tools that producers of mainstream music don’t use.

Glass Animals find a way to keep the clean, production-quality sound of compression while still featuring volumetric5 flexibility in their music. This, I think, is key. Because as fun as it is to have a dynamic, rousing song…I’ll admit that it must be pretty hard to write decent code when the music major you work with thought 1850s classical was the vibe for the day.

This may be a strange thing to remember, but if I learned anything through my major it’s this: music doesn’t evolve unless composers are willing to get real weird with it. Sometimes it works. Sometimes, it really, really doesn’t.

If I could embed music into a newsletter, I would start blasting “Tokyo Drifting” right now.

If you want to get technical, the “Radioactive” choruses are slightly louder than the verses (just check the waveform). But Glass Animals heighten the difference between sections so much that it’s actually noticeable in your ears.

I am aware that this is not the correct use of the word volumetric.