“Here it comes,” I said.

“Okay, now,” I promised.

“It must be soon,” I begged.

“I’m sure it’ll—”

I was listening to a new song, which will remain unnamed (I have forgotten the title), and I felt offended by its lack of substance. It was repetitive to a fault and, despite having the ingredients for a powerful build, seemed content to simmer away at a level just below exciting.

This is not a rare phenomenon. Countless songs have fallen victim to formulaic, non-creative songwriting that spews out just-okay tracks for tremendous profit. But where do these songs go wrong? Why are they so…meh?

Certainly, there is no clear answer. I won’t pretend to have one.

…

…

Okay, fine. I blame the second verse.

You see, there is a question that has haunted songwriters for eons. Many have fallen to its devastating implications. Those that ignore it inevitably produce mediocre work, while those that bravely confront it find their reward in excellence. The question is this:

“Why should this song continue?”

If, at any given moment in the song, this question cannot be answered with confidence, the songwriter has failed. If you can’t tell me why a work should continue…then it shouldn’t continue. This goes for everything from classical symphonies to modern pop singles. From the very beginning of the piece, it must make a case for its existence.

In classical music, this is done very methodically. Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony (you know it, I promise: dun dun dun DUNNNNN) starts with an ambiguous tonal center, or key, as we’ll call it. Without getting too in the weeds, we don’t know if the piece is in E♭ major or C minor, since the opening notes could be used in either key. Immediately, Beethoven presents us with a reason to keep listening: we want to know where “home base” is. Even though this happens without us consciously thinking it, something pulls us along and keeps us invested in the song. Even if we can’t put it into words, we can feel it.

Modern music does the same thing in different ways. Often, a modern pop song’s reason for existing is along the lines of “but wait, there’s more!” It will build in intensity and energy until the final, climactic chorus. Assuming a typical form of verse-chorus-verse-chorus-bridge-chorus (ABABCB), we can model the “energy” level of a pop song like this:

This is, of course, subject to change. The main idea is simply that one way for a song to earn its runtime is for it to build (or in some way develop) over time. If this plot is too flat for a given song, the track gets boring.

With this in mind, we can turn to the most crucial component of this delicate structure: the second verse. You see, the second verse must grapple with three equally crucial responsibilities.

1. It must sound like a verse.

2. It must carry forward the energy of the first chorus.

3. It must motivate the next chorus.

A song lives or dies by its second verse. In the case of a song that stays too flat, you can often trace the root of the problem to the treatment of Verse 2. And in the case of a song that grips the listener from start to finish, we can often thank the presence of an effective second verse.

Part 1: A verse is a verse is a verse

The second verse must sound like a verse; this much as always been clear to those who study music. The verses ground the listener in the structure with which we are familiar. Whether we’re aware of it or not, we instinctually expect songs to fall somewhere near the ABABCB model I’ve outlined above. I am of course speaking generally here and focusing mostly on “radio music”—songs you’d hear on the radio at any given time.

Some songs feature more sections. The most common of these additional sections is known as a “pre-chorus,” and it serves to ramp up the energy from the verse to prepare us for the chorus. There is also the “post-chorus,” which takes on the opposite role: it lowers the energy to set up the second verse. But if these additional sections are too long, or too numerous, the listener gets lost.

The verses are our footholds in the song; they are moments where we can catch our breath and take stock of our situation. Without clear verses, we might lose track of what the chorus was. Was it the second section, or the third? What should we be expecting to return to? In some songs, this ambiguity works. But most of the time, it is beneficial to ground the listener by offering them an obvious second verse, one that promises a return to the chorus we just heard.

Part 2: 2 be or not 2 be

Recall the age-old question: why should this song continue? At the end of the first chorus, the track is put to its first major test. It can, of course, copy and paste the sound of the first verse as a way to link choruses. Many songs take this route, echoing the mantra of “don’t bore us, skip to the chorus.” To this I say: please stop. If the second verse sounds identical (musically) to the first, it better have lyrical content that enriches and advances the meaning of the song. Otherwise, we are stuck in a sort of stasis, dragging our feet in the hopes that another chorus will come and save us. That’s no way to live. No, the most effective second verses will build upon the first verse by using what we “learned” from the chorus. In this way, the song has a reason to continue. It keeps going because the new sections learn from and develop off of the previous ones.

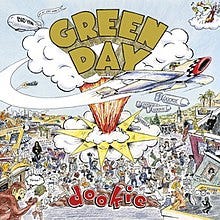

Exhibit A: “Basket Case” by Green Day

The first song that piqued my interest in second verses, “Basket Case” features a simplified first verse with just palm-muted guitar and vocals. Drums, bass, and full chords come in for the chorus, after which the guitar plays full chords on its own before a bass lick and drum fill launch us into the second verse. This transition between the first chorus and the second verse is one of my favorite moments in any song ever. The second verse maintains the chord progression and melody of the first verse, thus clearly marking it as a verse, while incorporating the fuller sound of the chorus. It keeps the energy trajectory of the song rising, and confidently says: yes, this song should continue.

Exhibit B: “Nearly Forgot My Broken Heart” by Chris Cornell

This song follows a similar trajectory to “Basket Case.” It starts very simply, but builds over the course of the first verse. The verse introduces us to the mandolin and bass, then the chorus shows us percussion and guitar. This song features a post-chorus, a brief moment after the chorus that returns us to the original opening sound: just a mandolin picking away. This offers a brief reminder of what the first verse sounded like before we JUMP into the second verse. Again, the song uses the same melody and chord progression as the first verse, but heightened percussion and more strings make this verse much higher energy and more exciting. The result? The song should continue!

Exhibit C: “Think” by Aretha Franklin

“Think” faces a different challenge: after a brief intro, it kicks off with nearly full energy. The first verse features (almost) every instrument that the song will use throughout the song. When we get to the chorus, we bring in horns and a climbing melodic line to add energy. But then what? How can Aretha elevate the second verse so that it supersedes the first, while still propelling the song forward and sounding like a verse?

Easy. She makes like a landlord whose tenants are locked out of their apartment, and opts for a key change.

The first verse and chorus are firmly rooted in B♭ major. After the first chorus, there is a very clear out-of-place chord. If you listen to it, you’ll hear it. It’s launching us out of the known tonal center and into a new one: B major. It’s not far away (we only move up a semi-tone, if we want to get technical), but we notice and feel it. The song moves up in pitch, and in doing so moves up in energy. You can’t just throw a B major chord in there and then end the song. No, no! It must continue!

Part 3: Motivational (bluetooth) speaker

We’ve spent a lot of time discussing how the second verse must provide a reason for the song to continue. In addition to motivating its own existence (by being sonically different from the first verse) it must also motivate the subsequent chorus. If the second chorus is copied-and-pasted after the verse, just there because that’s where it’s supposed to be, the song feels static again.

But how can the verse motivate the chorus? In my view, there are two ways. One is to build up to it, and the other is to recontextualize it.

The build-up is fairly self-explanatory, and often accomplished using an aforementioned pre-chorus. In “Temples of Syrinx” by Rush, the chorus is motivated by a simple guitar riff at the end of the verse. (In general, this song is a wonderful example of how to not waste a verse. The verses in this song rock even harder than the chorus.)

The more sophisticated approach is not just to build to the chorus but to actually recontextualize it. In this way, the repetition of the chorus doesn’t feel so repetitive.

Bo Burnham is a comedian who features music heavily in his sets. He writes comedy songs that frequently follow the exact structure we’ve been discussing: ABABCB. In his case, recontextualizing the second chorus is an absolute necessity, since often the chorus is the punchline to some kind of joke set up in the first verse. Needless to say, you can’t use the same punchline twice. Therefore, he has to make it so the second chorus (which, lyrically, is usually the same as the first) actually offers a different punchline. He does this in his treatment of the second verse.

Exhibit D: “Kill Yourself” by Bo Burnham

This song, from his special Make Happy, is off-putting to say the least. In it, Burnham discusses how many pop songs offer trite advice to those suffering from poor mental health and depression. He argues that one should not heed these songs, because often the advice is more harmful than beneficial. To satirize this, he uses the first verse to sarcastically empathize with his audience: “Have you ever felt sad and lonely? / Have you ever felt two feet tall?” He fills the first verse with a plethora of cliché statements (found in numerous pop songs), and then sings: “If you don’t know where to go, I’ll show you where to start…”

This is where Katy Perry might tell you to “Roar,” Sara Bareilles might encourage you to be “Brave,” or some other pop artist might offer a similarly asinine solution to a serious problem. Bo takes a different (yet arguably similar) approach. He tells the audience, “I’ll show you where to start…Kill Yourself.” The chorus of the song, which repeats these two words, is the punchline to his set-up, shining a spotlight on how these songs offer terrible advice to those who desperately need help.

However, even though the chorus is the punchline, it doesn’t exactly get a laugh. In fact, the audience nearly falls silent. This is, of course, to be expected given the subject matter. Bo acknowledges the audience’s reaction to the song (“I feel like you’ve pulled back…”) and then explains the thesis of his song: “that life’s toughest problems don’t have simple answers. You shouldn’t just be ‘Brave,’ you shouldn’t just ‘Roar,’ you shouldn’t…‘Kill Yourself.’” The second verse then changes the whole tone of the song. Bo sings about how serious suicide is and how signs of depression often go overlooked. He explains that if you are in need of help, you should pursue therapy and seek help from a professional. But, he warns, “if you search for moral wisdom in Katy Perry’s lyrics…then—” and we’re BACK to the chorus.

Only this time, the audience doesn’t go silent. No, this time they cheer. It’s the same lyrics as the first chorus, but he has entirely recontextualized them.

So why the cheers? The first chorus worked on shock more than anything, and even then, it barely got a laugh. The second verse’s role was to take this wildly offensive chorus and recontextualize it in a way that the audience could laugh at it. When Bo works it back around to the chorus, the huge reaction is an indication that he has succeeded. The audience is impressed that he dug the song out of its weird hole. This is why, if you watch the show, you’ll find just how much stronger and positive the audience reaction to the second chorus is. That isn’t because the second chorus is good; it’s because the second verse was perfect.

I used Bo Burnham to illustrate the concept of recontextualizing the chorus. In his work, it is very evident how important this is, because the same punchline won’t work twice if it’s treated the same both times. But that isn’t to say that this recontextualization only occurs in comedic songs.

Exhibit E: “The Chain” by Fleetwood Mac

Here’s an admittedly strange choice for a piece about second verses. You see, this song’s second verse is almost exactly the same as the first. How can it recontextualize anything?

“Listen to the wind blow / Watch the sun rise.

Run in the shadows / Damn your love, damn your lies.”

This is the first verse. From that initial line, we know that this song is about silence. “Listen to the wind blow...” implies a scene so quiet, you can actually hear the breeze. This is emphasized by the image of the sunrise, a famously quiet event. Even “run in the shadows,” a fun way to say living in the dark, suggests a hesitance to voice the truth. All this emphasizes that the relationship in the song is broken, but no one is willing to say it aloud.

Then we get the first chorus, an airing of grievances against the singer’s unsatisfactory partner. From the first verse, we know that this is meant to be thoughts swirling around in the singer’s mind, lurking under the surface but never seeing the light of reality. It’s a silent stewing of anger and resentment.

“Listen to the wind blow / Watch the sun rise.

Run in the shadows / Damn your love, damn your lies.

Break the silence / Damn the dark, damn the light.”

Here’s the second verse. As you can see, it is largely the same as the first. There are only two new lines, but they are essential to recontextualizing the second chorus. “Break the silence,” specifically, lets us know that we’re transitioning out of the singer’s mind and into the real world. The chorus now takes on a different vibe. Now, the silence is broken. We are no longer pushing our grievances to the back of our mind; now, we’re shouting them, full force, at the accused.

Well, folks, there you have it: a tribute to the unsung (ha!) hero of great songs everywhere. The second verse propels the song forward and often provides an answer to the eternal question: why should this song continue? So next time you listen to a song, listen specifically for the second verse, and decide for yourself whether or not it’s being used effectively.

PS. For anyone on their way to trivia night, Beethoven’s Fifth is in C Minor.