Mountains, Mole Hills, and the Uncivilized Mess of Civil War (2024)

The movie is about NOTHING, Jerry!

Is all art worth analyzing?

And if not, which art is? How do we decide whether a creative work merits deeper consideration?

Analysis is an act of trust. Last month, when I dug through the main theme of Severance, I was trusting that there is something there for me to uncover. In the same way, any time I engage critically with a movie, show, or song, I’m entering a social contract of sorts with the creator: They instill purpose into their art, and I try to find it.

Needless to say, not everything exists with such purpose. And yet, it’s easy for someone like me to construe an offhand decision into some grand gesture of meaning.

I bring this up because today we’re going to examine a movie at odds with the very concept of analysis. It’s a blatantly empty film—a superficial instigator that actively precludes deeper consideration.

But as hollow as this movie purports to be, and as glaring as its lack of ideas is, I still think there’s something going on. Something worth analyzing.

So grab a camera and fill your tank, because today we’re driving headlong into Alex Garland’s visceral epic: CIVIL WAR (2024).

Full spoilers for CIVIL WAR (2024) are coming, so now is a good time to swap your fluorescents for kevlar.

Part I. What is going on?

Civil War opens with an address from President Ron Swanson, in which he exposits the following:

There is a civil war in the US.

The Western Forces (WF), a military alliance between California and Texas, are leading a secessionist movement against the federal government.

The Florida Alliance is also a thing.

It’s an intriguing premise that begs many questions, such as:

Why is there a civil war in the US?

Why would California and Texas team up?

What’s going on with the Florida Alliance?

Unfortunately, Civil War will not be taking questions at this time. This is all of the information we’re going to get. The rest is up to us to interpret.

The film follows a quartet of journalists as they travel from New York to Washington D.C, encountering combatants from all sides of the polygonal war. There’s a firefight between men in uniforms and men not in uniforms. There’s a sniper contest between two guys in uniform and one person we never see. There’s Jesse Plemons playing a psycho as only he can.

Occasionally, the journalists voice the question that the audience is asking: “Whose side are you on?”

There is never an answer.

Civil War finds exposition abhorrent, opting instead to show only what is happening right now. The context doesn’t matter. Look at this, director Alex Garland seems to say, and make what you want out of it.

It’s up to the audience to interpret.

Part II. Who are these people?

We know some stuff:

Lee is a well-known war photographer.

Joel is an interviewer who works with Lee.

Sammy is an old man.

Jessie is an amateur photographer who idolizes Lee.

We also learn that Jessie’s family lives on a farm in Missouri, pretending the war isn’t happening.

We learn that Joel loves violence (“this gunfire is getting me extremely f***ing hard”) and desperately wants to interview the president before the war ends.

We learn that Sammy is wise and kind.

Then, at some point, Jessie asks Lee about herself.

Jessie: “How about you tell me the story of how you became a photojournalist?”Lee: “You don’t know? I thought I was one of your heroes.”

Have I mentioned how much this movie hates exposition?

After Sammy dies, Jessie and Lee have a short conversation about him.

Jessie: “I hardly knew Sammy compared to you, but—”

Lee: “No, you knew him. The man you were with…that’s who he was.”

This is meant to be sweet. Sammy was a great guy in the short time we’ve known him, and Lee is trying to say that he was a great guy all the time.

But this also reads as a meta description of the film’s characters. They lack depth and nuance. The people we’ve been with for the last hour…that’s all they are.

Part III. What’s the point?

A while back I argued that good movies make arguments. They have some issue they interrogate over the course of two hours, and they arrive at some conclusion. Then the audience is left to consider whether or not the argument was effective.

I’ve watched Civil War twice now. I’ve turned it over and over in my mind. And reader…there is no argument in sight.

Civil War doesn’t endorse the WF. It’s not concerned with the Florida Alliance. It apathetically mentions that the president is in his third term, has shut down the FBI, and is executing journalists…details which never resurface and are neither judged nor considered.

Meanwhile, the journalists themselves are embittered, war-loving adrenaline junkies. We see Jessie morph from a scared amateur to a manic bloodhound as she chases armed forces through the streets of DC. We see Joel savor the sounds of gunfire and agony, all while creeping on Jessie.

When Lee considers what life would be like without the war, Sammy notes:

“It wouldn’t have suited us anyway, Lee. We’d have gotten bored.”

These aren’t heroes by any traditional definition. They aren’t villains either. They’re just…there. Are we supposed to draw some broader conclusion about journalism from these one-dimensional plot devices?

What about the war? Is Civil War an anti-war film?

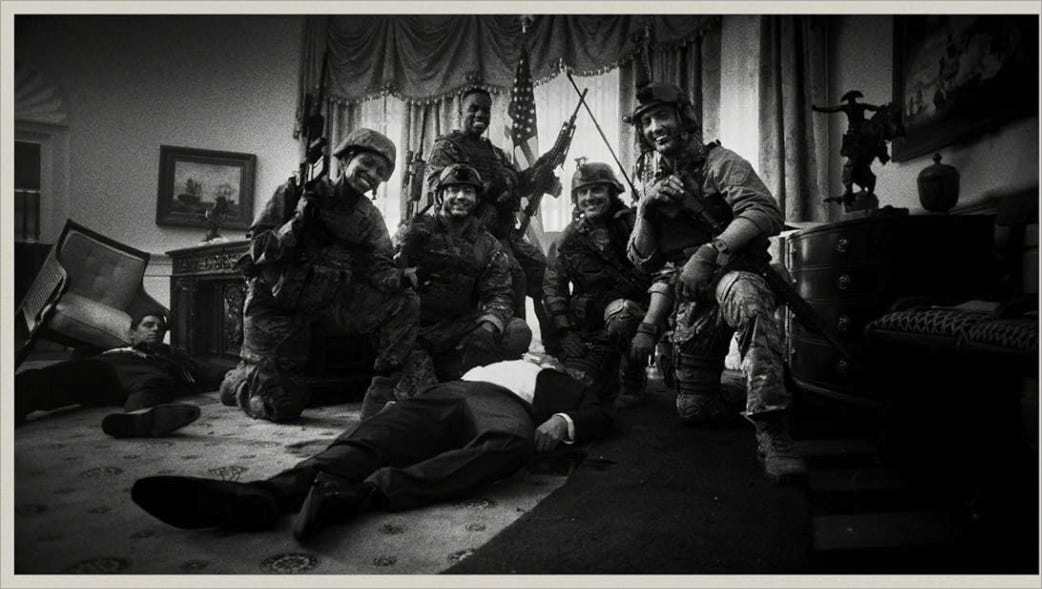

Even this is not clear. Horrific scenes are shot in beautiful slow motion. Senseless violence is accompanied by upbeat music. Tortured innocents hang from a broken-down car wash. Bodies fill a mass grave. Snipers don’t know who they’re shooting at. Operatives smile for the camera as they pose with the dead president.

Do these things point to an argument? Not a cohesive one.

But they do make me ask questions.

Part IV. What’s this movie about?

Civil War is about journalism.

And it’s about war.

And it’s about journalism during a war.

But I think the crucial theme that develops over the course of the film is that of journalistic neutrality.

Early on, Lee experiences flashbacks brought on by post traumatic stress disorder. For a few harrowing seconds, she relives moments from her life as a war photographer.

People are beaten, shot in the head, and killed right in front of her. She photographs them all, moving in close to the violence to get a good image.

A man is doused in gasoline and lit ablaze. He stares into the camera in agony.

Into Lee’s camera, yes. But also Alex Garland’s.

Journalists don’t get involved. They take pictures so that other people get involved.

“Once you start asking yourself those questions, you can’t stop. So we don’t ask. We record, so other people ask. You want to be a journalist? That’s the job.”

And so, Alex Garland (the writer/director) does as his characters do. He revels in violence. He perfectly frames a shot of a mass grave. He gets in close to a ruthless execution. He shows us what is going on with no context or commentary.

Here’s an image. Make of it what you want.

It’s an argument with no thesis. An essay with no conclusion.

He wants us to ask questions.

He wants us to interpret1.

In the film’s opening scene, a bomb detonates in the middle of a crowded protest. Lee whips out her camera and prowls through the wreckage, snapping photos.

Jessie takes a photo of Lee taking photos.

Alex Garland films Jessie taking a photo of Lee taking a photo.

The movie is reporting. Garland inserts himself into the film as a fifth, unseen journalist.

Jessie: Would you photograph that moment if I got shot?

Lee: What do you think?

When the roles reverse in the end and Lee leaps between Jessie and an assault rifle, Jessie is quick to yank her camera around, frame the shot, and photograph the moment.

Alex Garland is quick too. In slow-motion, and then stop-motion, we watch as Alex photographs Jessie photograph Lee get shot.

And then, perhaps more importantly, we watch as Joel pulls Jessie to her feet so they can move on from Lee and finally get what they came all this way for. And we ask ourselves one final, crucial question:

Was it worth it?

If you liked this post, you might also like this post where I break down a slightly different civil war:

Or this post where I talk some more about un-analyzable art.

Even the font choice, of both the main title and all location captions, is uninterpreted. It’s a generic, monospaced font like what you would find in a screenplay. Otherwise, the title card could provide a form of commentary on the events unfolding in the movie.