Take Your Time: The Pitfalls of Efficient Storytelling

On House of the Dragon's exercise in excess.

There’s a golden rule of screenwriting. It comes in a variety of forms, but every version drives at the same piece of wisdom:

Trim the fat.

Start late, end early.

Leave them wanting more.

Don’t strand your most interesting character in a haunted house for five straight episodes.

Regardless of phrasing, the takeaway is the same: stories should be efficient.

It is the writer’s job to know exactly what story they’re telling, and then tell exactly that story. For example, if a character in a movie realizes that a clue is across town, we don’t need to watch them tie their shoes, get in the car, and sit in traffic. It would be much more engaging to start the scene right when they pull up to the relevant location.

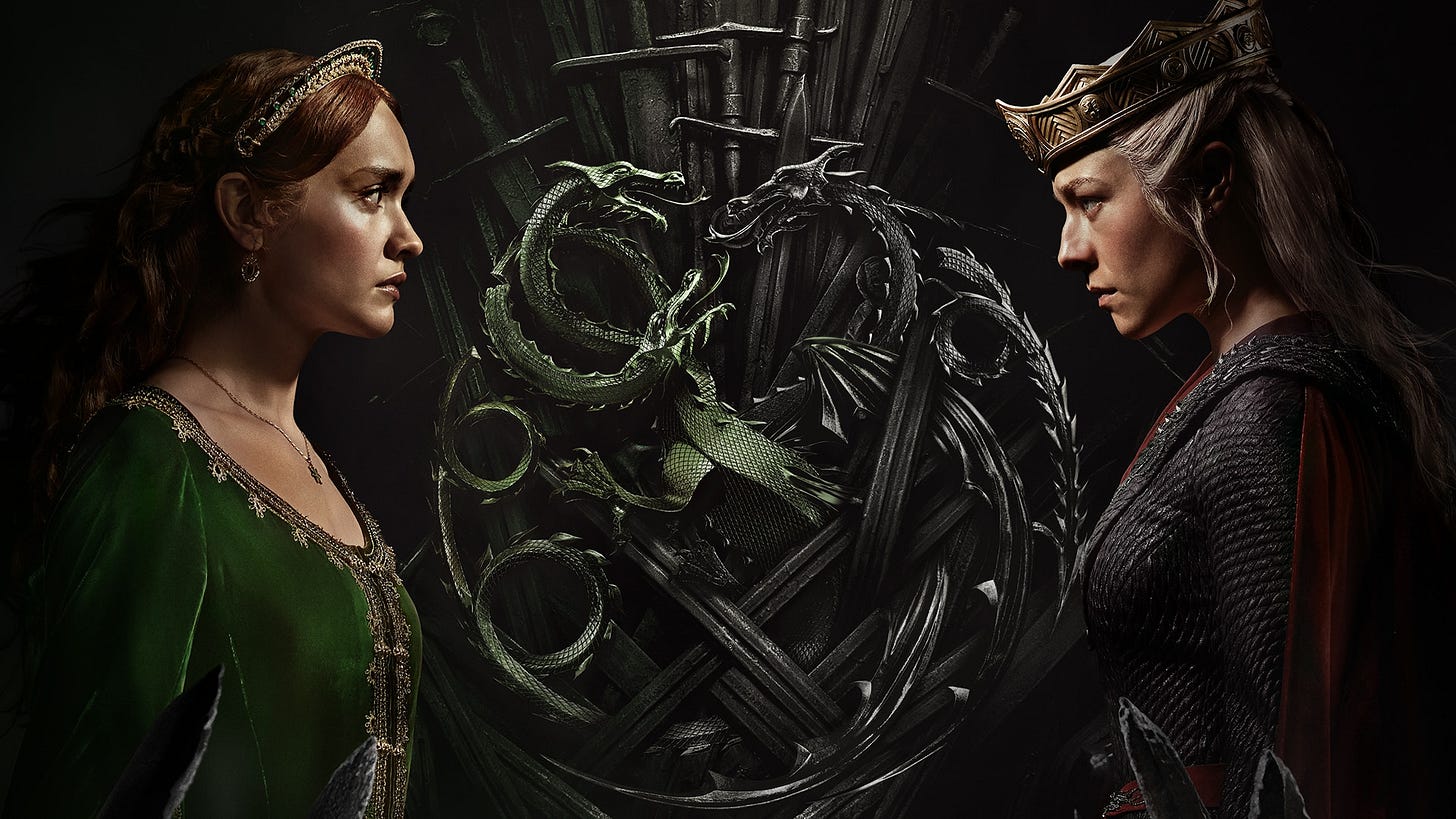

This brings us to HBO’s House of the Dragon, a series that seemed to take our golden rule and rudely dump it over our heads. The show, which recently concluded its second season, divided fans and critics alike with its choices to prolong uninteresting plotlines and allot valuable screentime to tertiary (even quartiary) characters, all while omitting key battles and set pieces in favor of hushed conversations and vague political scheming.

These decisions reached a polarizing head with the season finale. After an extended montage of our characters suiting up for what promised to be a critical fight in the Dance of Dragons, the episode…ended. The noteworthy lack of any sort of climactic battle ruffled scales across the Seven Kingdoms and prompted a number of news outlets to resurface reports that the writers of HOTD were restricted to eight episodes on account of the writers’ strike last summer.

In fact, the aftermath of HOTD’s finale has seen an inordinate amount of coverage regarding the machinations behind the series, from the diminutive episode count to the reported budget of those episodes. It seems that people are searching for an explanation to excuse the controversial decisions made by the writers and producers.

But what if, I ask you, the creators made those choices in the interest of good writing, and not strictly good business?

What if, at the end of the day, the story the writers want to tell is different from the story we want to watch?

I did not like the first season of HOTD. I found it remarkably slow, unnecessarily verbose, and frustratingly boring. It was a whole lot of build up to a whole lot of nothing.

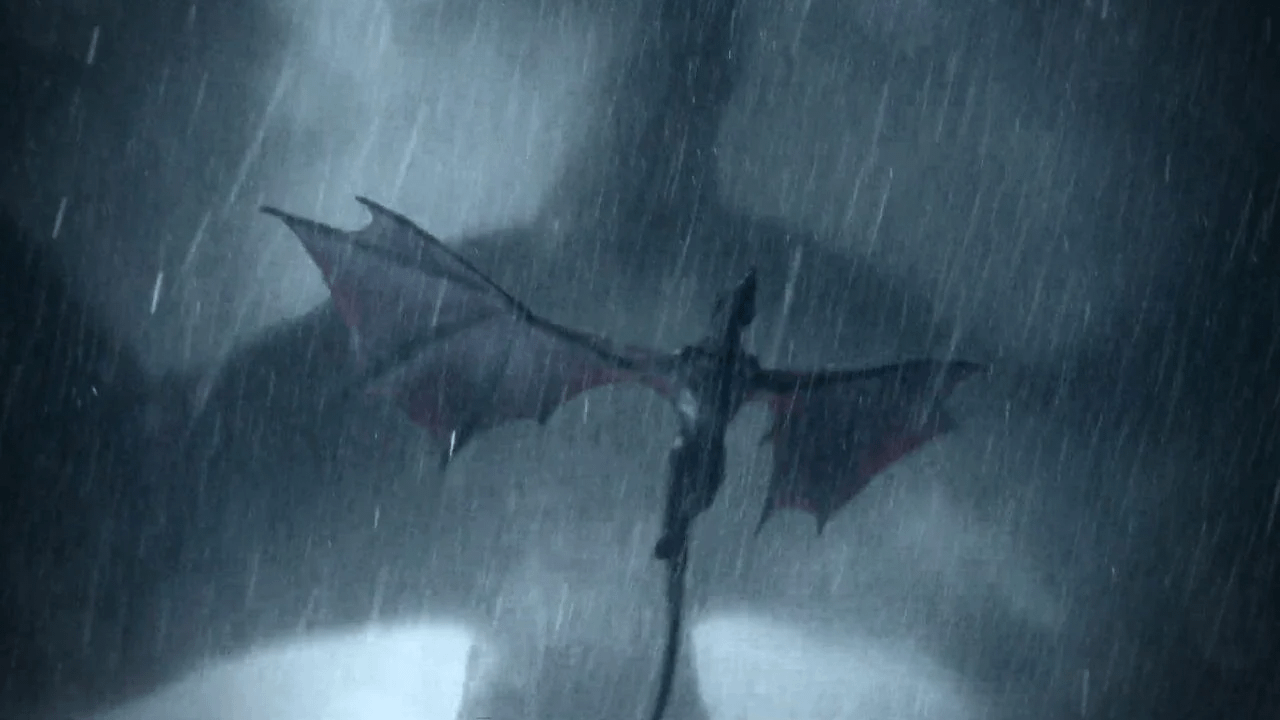

But I had to admit that at the end of Season 1, the story was in an interesting spot. The death of Rhaenyra’s son Luke (he’s on the small dragon, above) felt like the spark that would ignite the war in earnest. Everything was in place for Season 2 to blow us away with the fire-breathing carnage we expect from a show called House of the Dragon.

However, despite this powder keg set-up, the second season opened with more of the same disappointing sense of stasis that plagued the first. In the premiere, no one wants to make the first move until Daemon sneaks into King’s Landing and enacts a plan that leads to the beheading of King Aegon II’s son.

The show treats this event like a big deal. They killed the king’s son! Now there will be war for sure!

But, you may be thinking, as I was, isn’t that exactly how the first season ended?

This sort of thing is commonplace in HOTD. The show loves to crescendo to big moments—think of Rhaenys illegally parking her dragon at Aegon II’s coronation—only to allow them to fizzle out with no apparent consequence. It’s frustrating, and the fact that Season 2 continued the trend disappointed me greatly.

And yet, spurred by the cultural phenomenon and the dream of what the show could be, I continued tuning in week after week. The second episode felt much like the first. The third, in a display of outright obstinance, cuts from a petty land dispute to a war-ravaged battlefield, glaringly omitting the actual fight.

But something else happened in episode three.

Something that changed the way I viewed the show.

“Soon they will not even remember what it was that began the war in the first place. [Was] it when the child was beheaded? Or when Aemond killed Luke? Or when Luke took Aemond’s eye? We teeter now at the point where none of it will matter, and the desire to kill and burn takes hold, and reason is forgotten.”

This dialogue, delivered by Princess Rhaenys, struck me for two reasons.

First, it assured me that the writers have a plan. That they are showing us everything for a reason. Because we watched Luke stab Aemond in the eye when they were ten years old. Then we watched Aemond kill Luke when they were older. And we watched through our fingers as Daemon’s plan went awry and the wrong son was slaughtered.

In the moment, any impact of these potentially catalytic events was immediately diminished by the show’s tendency to deescalate conflict and practice an irritating level of restraint. However, even when the consequences were buried in half-hearted attempts at diplomacy, they never truly disappeared. The benefit of hindsight allows us to view these events as small steps towards the inevitable war.

But more than that, Rhaenys’ lament colored the series in a new light—one that offers insight into the decisions made by the show’s creators.

“We teeter at the point where none of it will matter.”

Perhaps this is the very purpose of the show. They could cut out a bunch of stuff. It doesn’t really matter, from a historical perspective. They could start late and end early and we’d get the gist. We’d see the battles and watch the action and know who wins and who loses. But, instead, HOTD argues that the stuff that usually goes unseen and unheard matters too.

Even Criston Cole, the most hated man on the internet, makes some points in the Season 2 finale.

“You saw what I saw. The dragons dance, and men are like dust under their feet. And all our fine thoughts and all our endeavors are as nothing. We march now toward our annihilation. To die will be a kind of relief, don’t you think?”

Bleak words, Criston! But well taken. As soon as dragons pull up to a battlefield, anything happening on the ground becomes irrelevant. Shields and spears can only protect you against so much.

And yet, this show chose to forefront the humans in the story, not the dragons.

Let’s revisit that scene from episode three—the land dispute that turns into a battle. Two people bicker about their property before it becomes clear that they are on opposite sides of the Targaryan civil war: one supports Rhaenyra’s claim to the throne, and the other supports Aegon II’s. They argue, tensions rise, and one draws his sword.

Then we smash cut to the same location, but it has been destroyed by war. Bodies litter the blood-soaked grass. We missed the fight, sure, but we see the cause and we see the effect. That is what this show is interested in. Not the war itself, but the impact of the war on the people that find themselves in its path.

Even when we get a full blown battle in episode 4, the focus still lies with the people on the ground. For every epic dragon-on-dragon set piece, we are also forced to witness the horrors transpiring for the soldiers below. Criston Cole stumbles though the charred battlefield searching for survivors, only to discover ashes where men once lived and breathed. It’s a brutal depiction of a war waged with powers that humans cannot fully comprehend.

In light of all this, the initial claim that HOTD is an exercise in excess is not entirely accurate. They aren’t flouting the start late, end early mentality—it just that the story they are telling, of the loss of humanity and morality in the age of nuclear war, is not the story that the general audience expected (or necessarily wanted) them to tell.

To echo a chorus that has been repeated since the show first took flight: this is not Game of Thrones. While both HOTD and GOT center on ambitious, morally grey characters vying for power and control, the plots are, at their cores, antithetical. We tuned into Game of Thrones to see who would win; we watch House of the Dragon to see how everyone will lose.

So yes, we may have started way too early for epic clashes and dragon-ridden battles. But we were right on time to witness the decline of an empire via a world-shaking civil war. Ultimately, HOTD presents a strong, undeniable thesis that no one wins a war by depicting the literal and moral collapse of all parties involved. And it does so while showing us as little of the war as possible.

Now that’s efficient storytelling.