If you leave a Netflix show paused for more than a few minutes, you will be presented with a curated screensaver of the platform’s top shows and movies, complete with the title and three applicable genres or descriptors to pique your interest.

This happened to me recently; I accidentally left the TV on and found myself catapulted into the depths of Netflix’s catalog.

I was intrigued by the genres that accompany each title. These shows are “Witty”. They’re “Irreverent". They’re “Adventure”, or “Teen”, or “Slick”.

But above all else, they are “Dramedy”.

Dramedy.

And as I sat on my couch floating down the endless stream of great TV, I suddenly arrived at a startling conclusion.

Genre is dead, and the dramedy killed it.

Part I. Origin Story

Before we can speak to the demise of genre, we must understand its inception.

The Greeks

Among their many other credits, the Ancient Greeks established a theatrical tradition that has persisted for centuries. The plays of Sophocles (Oedipus Rex, 429 BC), Aristophanes (The Clouds, 423 BC), and Euripides (Medea, 431 BC), to name a few, are still taught, read, and performed today.

We’re starting with the Greeks because they largely considered two different genres for their plays: tragedy and comedy.1

To them, the distinction was very clear. A comedy had a happy ending, while a tragedy did not. Easy!

The Bard

Let’s shimmy forward in time to to the 1500s. Bill Shakespeare is making rounds with his groundbreaking plays which were published under one of three genres.

Tragedy, comedy, and history.2

In other words, only one additional genre had resulted from over 2000 years of dramaturgical advancements.

Of course, Shakespeare’s comedies have sad, dramatic moments in them, and his tragedies include moments of levity. Even his histories weren’t always perfectly historical. But the genres still existed, and with them continued the same societal expectations: comedies have happy endings, tragedies have sad endings, and histories are…well, historical.

The Pioneers

Of course, tragedy and comedy are wide categories, and over the centuries it became necessary to introduce some subdivisions.

To name a few:

Samuel Richardson wrote Pamela, or Virtue Rewarded in 1740. This is the first known romance novel.3

In 1841, Edgar Allen Poe published “The Murders of the Rue Morgue,” a short story which is widely considered to be the first mystery/detective story.4

Phantastes, penned by George MacDonald in 1858, can be argued to be the first fantasy novel.5

Needless to say, this list gets rather long rather quickly. After all, every genre started somewhere.

The important thing to consider is that with every new genre, a framework is created. A romance story will include characters who fall in love. A detective story will feature a mystery that needs to be solved. A fantasy story will introduce us to a new, unseen world.

And, as always, a comedy is happy, and a tragedy is sad.

The creation of these frameworks is, in effect, the entire purpose of genre. By categorizing a play or a book under a widely understood label, consumers know what they’re getting into. This way, someone looking for a book about a colorful, exciting fantasy world won’t open Fifty Shades of Grey instead.

Part II. Whodunnit

Et voilà: it’s now the 21st century and we have genres. Lots and lots of genres.

You’ve got your action comedies, your psychological thrillers, your film noir, your science fiction, your musicals, and so on.

But here I am, arguing that genre is dead. What happened? Who killed genre?

The Problem

The problem with genre is also the reason it exists in the first place: those darned frameworks.

Let’s say I want to watch a movie where two people fall in love. What genre should I look for?

Well, do I want the two people to stay together and get into some silly antics along the way? Then I head over to Netflix, search for RomComs, and settle in.

Or do I want something messier, where the relationship causes conflicts that ultimately drive the characters apart? Why, that would be a romantic drama—I’ll find a good one, grab some popcorn, and ready the tissues.

Do you see the problem?

Genres are the ultimate spoilers.

The Solution

Let’s be clear here: not every movie conforms strictly to genre. Filmmakers have known for decades that audiences go into a story with preconceived notions of the film they’re about to witness.

If it’s a comedy, I’m expecting to laugh.

If it’s a drama, I’m expecting to cry.

That’s why so many movies have turned these expectations on their head.

The Other Guys (2010) is a comedy about two cops that get in way over their heads. Of course you laugh throughout it, but the last third of the film sneaks away from pure comedy and starts commenting on capitalism, corruption, and greed in a very poignant, not-particularly-humorous way.

Fargo (1996) is a drama about a man who hires two criminals to kidnap his wife. It’s also one of the funniest movies I’ve seen recently.

If you know what to expect and you get what you expect…it’s kind of boring. Alternatively, if you know what to expect and you get something different and better, it’s delightful. That’s why so many movies try to subvert the expectations of their genres.

We can trace this phenomenon of mixing genres back to Shakespeare, who put jokes in his dramas and deaths in his comedies. In fact, there’s a whole category of Shakespeare’s plays called the “problem plays” that don’t fit neatly into either camp6. We can even take it all the way back to Greece, where Sophocles wrote an ironic, even comedic misunderstanding into Oedipus Rex, a rather dramatic drama.

As I posited in my newsletters on writing funny scenes and writing sad scenes, tragedy and comedy are inextricably linked. You elevate one by including the other. A scene is funnier when the characters have been through hardship; a scene is sadder when they’ve known joy.

The Dramedy

This brings us back to my original gripe: “dramedy” is a meaningless word.

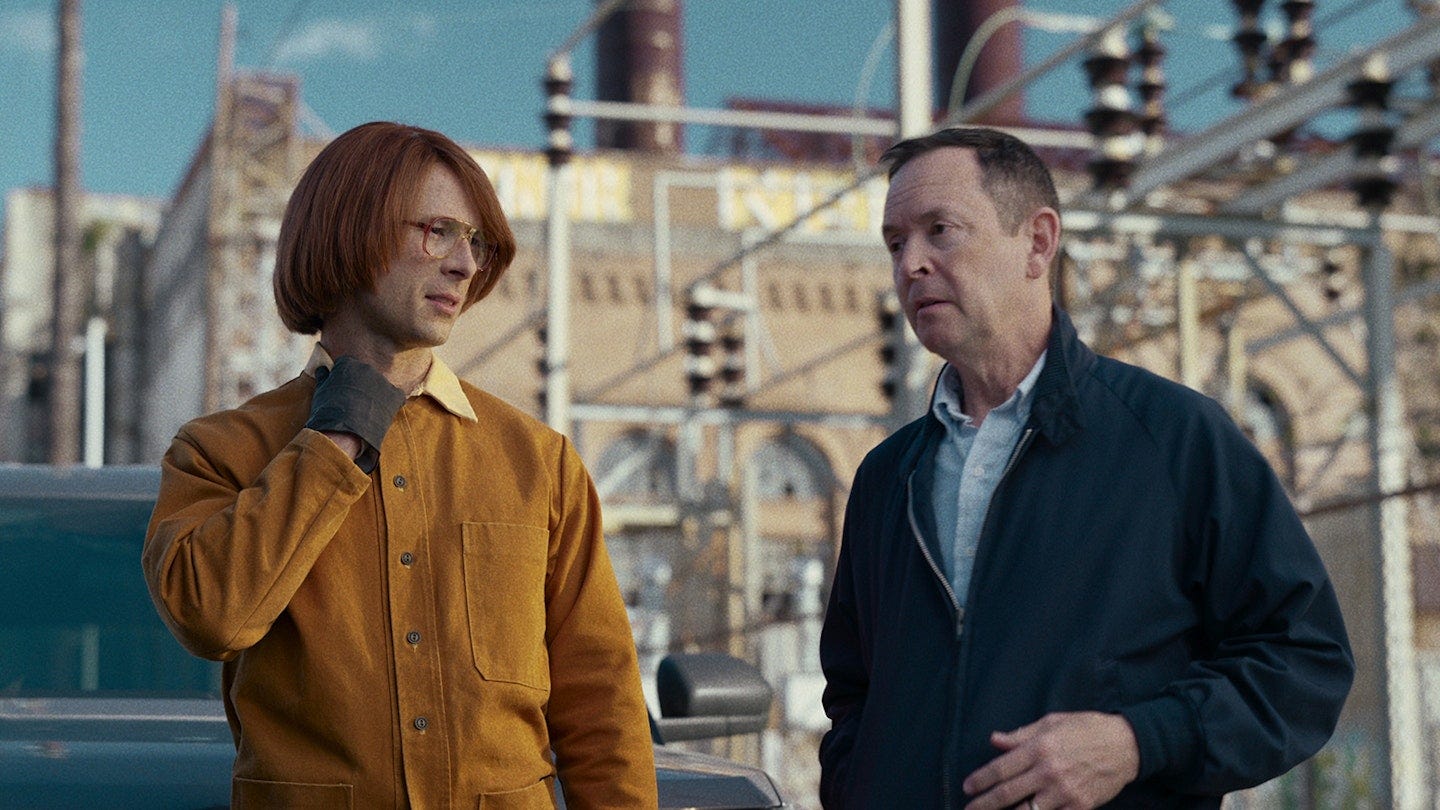

Take Hit Man (2024), the recent Richard Linklater/Glen Powell collaboration, which Netflix’s algorithm slapped with the dramedy label.

It starts out as a straight-up comedy. There are jokes and bits and costumes.

Then it becomes a romantic drama. There’s love and conflict and messiness.

And then it becomes a film noir/detective/crime film, with murder and intrigue and suspense.

It all works, because it operates under a unified tone and offers a clear theme to the viewer, but the genres are a mess.

And what do we do when genres are a mess?

We call it a dramedy, because everything that has ever been made can be called a dramedy.

Part III. Apocalypse

So…what’s next?

We started with two genres, which branched off into hundreds of sub-genres, which themselves developed sub-sub-genres.

Now, we’re experiencing a clear rejection of the very concept of genre. “Dramedies” are the most common media you’ll encounter today. Hit shows like Succession, Barry, and The Bear feature dramatic set pieces followed by laugh-out-loud comedy. Mainstream films like Barbie (2023), The Holdovers (2023), and, yes, Hit Man, pull off similar balancing acts.

The very idea of genre has been weaponized into red herring; it’s a device which filmmakers can use to throw the audience off the scent. Rian Johnson's Knives Out (2019) was marketed as a whodunnit. Then, 45 minutes into the movie, he tells us exactly who did it. Then, 90 minutes into the movie, we realize that there actually was a different whodunnit happening under our noses the whole time.

Today, this kind of innovation and subversion is appreciated and applauded. We are experiencing a shift into a post-genre entertainment industry, in which audiences are thrilled by the twists and turns that veer out of predefined frameworks and into untrod territory.

But what happens when the novelty wears off? When the dashing of expectations becomes the expectation?

Ultimately, this is a question that will be answered by the writers.

Although we write about our own experiences, the resulting story is inherently informed by the stories that were first told to us. This is the true cause of our post-genre society: writers grew weary of repetitive tropes and began exploring ways to overhaul them.

Taste in the entertainment industry is not made by the consumers. Otherwise, Hollywood would be an endless echo chamber of last year’s hits. It is not made by the marketers or producers either, no matter how hard they try. No, the taste makers in the industry are the writers who tell the stories. It is up to them to respond to what has come before and create something fresh and new.

We are on the precipice of a new age of cinema in which genres grow increasingly irrelevant. Films will continue to merge, blend, and twist the tropes that once defined them, creating new stories that refuse categorization.

In other words: genre is dead, and the dramedy killed it.

…

But maybe that’s not a bad thing.

https://www.pbs.org/empires/thegreeks/background/24c.html

https://www.bellshakespeare.com.au/genres-of-shakespeares-plays

https://cristinharber.com/archive/evolution-romance-novel/#:~:text=The%20first%20known%20romance%20novel,and%20her%20land%2Downing%20master.

https://www.tiki-toki.com/timeline/entry/758542/THE-EVOLUTION-OF-GENRES-A-Sideways-Look-at-Literature/

https://fantasyliterature.com/reviews/phantastes/

https://blog.antaeus.org/blog/shakespeares-problem-plays/