808s & Film Tape: Sampling in Movies Scores

How Oppenheimer's composer Ludwig Göransson finds music in everything.

In the beginning, there was a dark room, an antsy audience, and a way-too-loud projector.

To drown out the grating sounds of heavy machinery, theater owners began hiring musicians to play live music, usually on a piano or organ, alongside silent films.

And thus, film music was born1 and quickly began to evolve:

Improvised music was written down for reproducibility at later shows.

Live music was swapped for pre-recorded cues.

Solo pianos gave way to quartets, which soon grew to full orchestras.

John Williams (Jaws, Harry Potter, Indiana Jones, and many many more) came around, scored every movie ever, and set the standard for what “cinematic music” sounds like with his neoromantic style.

Hans Zimmer (Interstellar, Dune, The Lion King, and many many more) brought us into the digital age by mixing traditional orchestral instruments with modern synthesizers.

And now, over the last decade, another key player in the history of cinema has emerged. He is changing the way we think about film music by stitching the very essence of each film he works on into his scores.

He’s the most exciting composer of our time, and his name is Ludwig Göransson.

Before we get into it, here are some things you should know about Mr. Göransson:

He’s a 39 year old composer and guitarist from Sweden.

He went to USC film school, where he met Ryan Coogler.

He has scored every one of Coogler’s films.

He wrote music for the show Community, where he met Donald Glover.

He has produced every one of Childish Gambino’s albums (and co-wrote many songs).

With this background in mind, let’s check out his work.

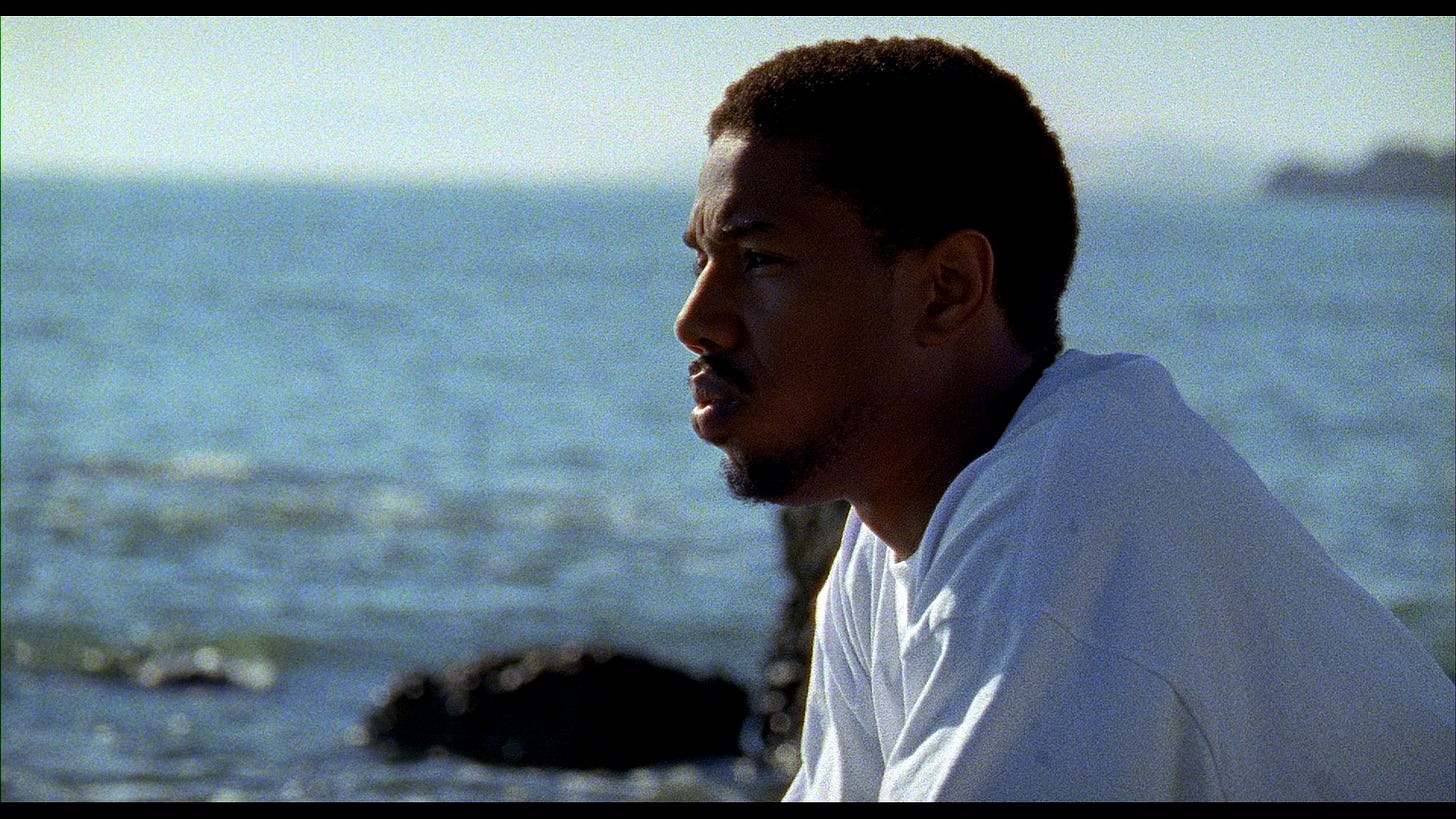

Fruitvale Station (2023)

Ryan Coogler’s (and Ludwig Göransson’s) first feature film tells the true story of Oscar Grant, a black man who was fatally shot by police in the Fruitvale BART station in Oakland, CA.

It’s a low-budget film, meaning that Göransson likely did not have access to a real orchestra or professional musicians. He had to work digitally.

And so he did. But he didn’t just use a generic synth to add texture and vibes to the score. Being experienced in music production (at this point he had already begun his professional relationship with Childish Gambino), he actually went to Fruitvale Station and sampled the trains as they passed by. Then, with his producing prowess, he molded these samples into the melancholy, atmospheric backdrop that underscores most of the film.

You can listen to it here.

Creed (2015)

First, make sure there are no breakable objects near you.

Then watch this.

Once you’ve had a moment to come down, ask yourself: how does Göransson imbue the film into his music?

I’ll give you a hint: listen to the bass drum.

Or should I say…punching bag.

That’s right, folks. Göransson’s score to Creed samples boxers punching heavy bags, jumping rope, sparring, and more. He used those sounds as the bedrock of the score, masterfully laying the orchestra on top to create an new, fresh sound for a classic franchise.

Watch the scene again; I bet you can hear the bass-drum punches.

Black Panther (2018)

Now an established filmmaker, Coogler was approached to make Marvel’s Black Panther. And of course, he asked Göransson to compose.

Just like their Fruitvale days, only this time, Göransson got a 92-piece orchestra and a 40 person choir to work with.

Try this scene on for size.

I may do a full deep dive on the Black Panther score in a future newsletter, so for now I’ll just point out that Killmonger’s theme is really three distinct themes which Göransson seamlessly blends together.

We start with the ambiguous, ascending scale. We’re not sure what to make of this guy yet.

Then we get the tambin, an African flute that suggests Killmonger’s Wakandan origins.

Then we get the 808s, which foreground his ties to Oakland.

And then we bring it all together in an amazing cue that showcases Göransson’s skills as both producer and composer.

No surprises that he secured his first Oscar for this one.

Tenet (2020)

Director-composer relationships are common in Hollywood.

Steven Spielberg and John Williams

Ryan Coogler and Ludwig Göransson

Christopher Nolan and Hans Zimmer

Hans Zimmer’s collaboration with Christopher Nolan has led to some of the most iconic film scores of all time, including the The Dark Knight, Inception, Interstellar, and Dunkirk. It was a surprise for many, then, that when Nolan announced his sci-fi-action-espionage-thriller Tenet, Hans Zimmer wasn’t listed as the composer.

It turns out, Zimmer had decided to work on Denis Villeneuve's Dune instead, and in doing so he left a power vacuum in the world of composing. Who could Nolan possibly choose to follow up Hans Zimmer?

I know who.

You know who.

Needless to say, Nolan knew who, too.

The truth is, I don’t even like Tenet that much. It’s a cool movie, with crazy action scenes and some really amazing set pieces, but even after a rewatch, I am entirely baffled by the film’s plot.

One thing is for sure though: Göransson’s music goes hard.

You see, Tenet is all about time inversion: the characters in the film often find themselves traveling backwards through time.

How fitting, then, that Göransson’s score would travel backwards as well?

Check out this cue:

Can you hear what’s going on?

“To create the feeling of backward music, Göransson had his musicians play some pieces normally, then he would reverse the audio recording and play it back for them and have them emulate what that reversed audio sounded like — and then reverse that recording.” - LA Times

He doesn’t stop there; some of the melodies that he wrote for the score are palindromes—the same forwards and backwards.

If you’ll allow a slight stretch, he “samples” the concept of the film, rather than its physical subject matter, in the music.

Oppenheimer (2023)

Finally, we arrive at the film that earned Göransson his second Oscar.

I really wish I could find the “Can You Hear the Music” montage on YouTube, but instead you’ll have to just listen to the music yourself and imagine it blasting as Oppenheimer becomes one with the universe.

It’s aggressive. It’s huge. It’s haunting. It’s anxious. It’s…mathematical?

That’s right. Inspired by old Oppie himself, Göransson crafts a theme built around math. He chooses a hexatonic scale (six unique notes) repeated over and over at various tempos. In fact, in this cue alone there are 21 tempo changes (one every seven measures). He also switches the groupings of the notes, frequently alternating between triplets and sixteenths.

In this interview, he explains these choices by comparing Oppenheimer’s pursuit of knowledge to learning a new instrument. As you learn a new song, you slowly work up the tempo until you can play it comfortably at any tempo you like.

In other words, Oppenheimer’s arc from student to master is mirrored by the score.

Göransson also employs several production hacks in the song. For example, rather than recording the strings and then laying in the synth over top, he actually blasted the synth in the room alongside the strings and recorded that, so that the digital sound would mesh better with the analog instruments.

The result is a sequence that gets your heart racing and mind reeling as you watch the glorious spectacle unfold before you.

What’s Next?

First it was John Williams. Then it was Hans Zimmer.

Now, it’s Ludwig Göransson’s time to push film music forward.

It’s one thing to write music that matches the emotion; it’s another to do it by sampling the subject matter of the film.

This is why Göransson’s scores are so engaging and unique. He extracts what makes a story special, whether it’s the setting, a prop, a concept, or a principle, and he incorporates it into his music in a way we’ve never heard before.

By working at the intersection of film music and popular music, he is able to bring production tricks into the orchestra chamber and make scores that are simultaneously familiar and new. He is writing music that is emotionally resonant, sonically satisfying, and technically impressive. He is a master of his craft, and he’s just getting started.

So I’ll say it again, louder for the people in the back: he’s the most exciting composer working today, and I can’t wait to hear what he does next.

Looking ahead…

Wash your hands and grab a bagel: next time, we’re diving into the Spiderverse.

The origins of film music are disputed. This is the most fun explanation. It’s probably not true.