What makes a movie good?

I ask this because I recently watched three movies that are considered by many to be good. These were three different movies with varying tones, plots, and genres. I watched each one and, at the end of each film, I thought to myself “Wow. That was good. I see what they mean.”

But what do they mean? For that matter, what do I mean?

What makes a movie good?

My default answer to this question has always been this: a movie is good if it makes you feel something.

But that’s a slightly flawed definition. Take a horror movie, for example, that succeeds in making you feel uncomfortable or scared but ultimately features a flimsy plot with meaningless characters. Is that a good movie?

I can’t and won’t say for sure.

What I can and will say is I was watching these three movies, I noticed a common thread that suggests one possible criteria for a good movie: a thesis.

One of the very first lectures in my very first screenwriting class revolved around theme.

“What are some examples of themes?” asked my professor.

“Love,” someone shouted out.

“Friendship,” volunteered another.

“Addiction.” “Grief.” “Forgiveness.” The answers kept coming.

My professor shook his head.

“Theme isn’t an abstract idea. Theme is a statement, an argument, and the goal of your movie is to prove that it is true.”

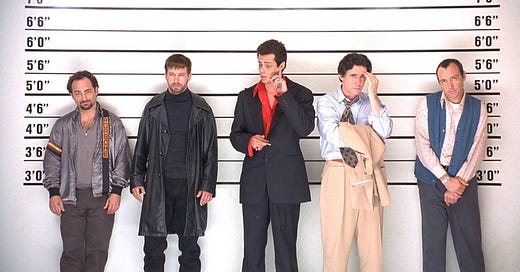

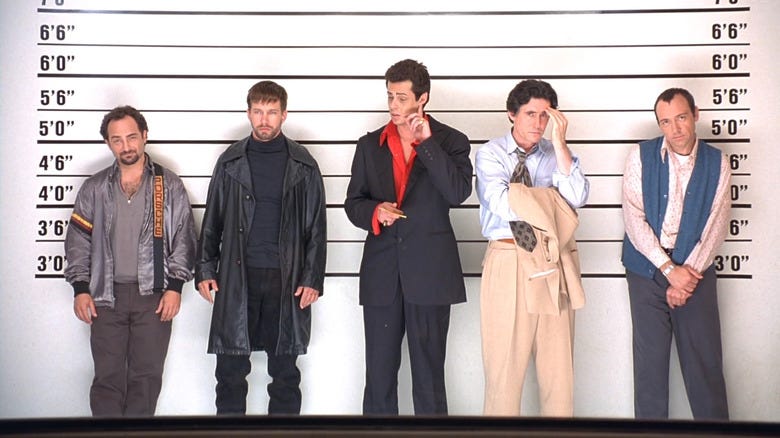

“The greatest trick the devil ever pulled was convincing the world he didn't exist.”

The Usual Suspects (1999) is a good movie.

And I’m about to spoil it so watch out.

The film holds lots of twists and turns along with fun action sequences and a thrilling climax. But above everything, the movie is held together by this central idea: the devil exists, but he wants (and needs) to remain in the shadows.

Throughout the film we are introduced to the character of Keyser Söze, a criminal mastermind who has lurked in the shadows for years. He’s a modern-day mythological figure—a bogeyman for criminals and law enforcement alike.

Thus, when the police officer interrogating Verbal asks if Söze is real, Verbal replies with an answer that has since become iconic: “The greatest trick the devil ever pulled was convincing the world he didn't exist.”

At this point, the trick is only “great” because it is successful: the officer’s doubt proves that Söze, if he is real, managed to convince the world he doesn’t exist.

As the film develops, we learn that the five men participating in the central heist have somehow wronged the legendary Söze in the past. Not only that, but since none of them really believe Söze is real, they all think they have gotten away with their transgressions.

Needless to say, they have not.

As Söze kills them off one by one, we are confronted with a deeper level to Verbal’s thematic quote.

The trick is great not because it is effective, but because, as long as the five men did not believe in the Söze, they did not fear consequences for their actions. This made them easy targets. Söze exploited their non-belief for his own benefit.

Then, in the last few minutes of the film, the interrogation ends and Verbal is released. He strolls out of the precinct in slow motion while the police officer undergoes a dramatic epiphany in which he realizes that the devil not only exists…but just walked out his door.

As Verbal, or should I say Söze, walks freely down the street, we hear his quote once again, this time as a voice over.

Quite a trick, indeed.

“I’m Shiva, the God of Death.”

Michael Clayton (2007) is a good movie.

Starting from Michael’s introduction in the movie and continuing through the climax, we are continually presented with a crucial question: Who is this guy?

Is he a fixer? A miracle worker? A janitor? Characters throughout the film use all of these identifiers (and more) to describe our protagonist, but none of them really seem appropriate. We’re told that Michael is this great problem solver, someone who comes in and cleans up messes made by his law firm.

But we never see him in action.

Even Michael doesn’t really know who he is. He has a wife and kid he neglects, a job he seems to loathe, and a mountain of debt from an ill-planned business venture with his bummer of a brother.

He spends the movie coming to terms with the dark nature of his work and the twisted, immoral actions of both his firm and his clients. He loathes his job, but he can’t bring himself to do anything about it because of his personal situation.

Until a poorly timed car bomb forces him to do something about it.

In the brilliant final scene, Michael uses his shape-shifting nature against Karen. He lists all of the identities that people have foisted on him throughout the film (“a fixer, a bagman, . . .”) and convinces Karen to incriminate herself to him.

And then, after revealing that his monologue was a sham and she has fallen victim to a classic blunder, he provides one final, climactic “I Am” statement that sums up his journey:

DON

Who are you?

MICHAEL

I'm Shiva, the God of Death.He’s calling back to a line uttered earlier in the film by Arthur Edens, a coworker at Michael’s firm who was murdered days prior because of his refusal to accept the shady work being done by his clients.

With this line, Michael cements his character arc, growing from a faceless “fixer” who is mired in an impossible situation to an agent of justice who is above the petty squabbles of humanity.

This is who Michael is.

“I just don’t understand it.”

Fargo (1996) is a good movie.

But it’s also a slightly confusing movie.

The Coen Brothers tend to do that to me—I often don’t really understand the point of their movies until the very end (or, if I’m being very honest, a few days after the end).

Fargo, for example, has some scenes that, in the moment, feel unnecessary. About halfway through, we interrupt the primary investigation to watch Marge grab lunch with Mike, a guy from her high school. Over the course of the conversation, he says that he is married, then tries to make a move on Marge, and then breaks down crying and admits that his wife has died.

Then we cut back to the main plot.

The lunch scene becomes even more confusing later in the film when Marge learns from a friend that Mike was never married. She, like me, is confused by this.

Then we cut back to the main plot and never hear or think about Mike again.

But it all comes together in this perfect scene.

There’s a lot of thematic material in here. Perhaps the real main theme of the movie is “There’s more to life than a little money, you know.”

But the more interesting line, the one that made everything click into place for me, is the final sentence:

“I just don’t understand it.”

Simple, poignant, and devastating. For me, this served as a skeleton key to the rest of the film.

We first meet Marge when she’s woken up early in the morning by a phone call asking her to come investigate the triple homicide that incited the film. Her husband wakes up too and groggily makes her some eggs before she departs.

Following this introduction, all depictions of Marge’s home life glow with warmth and happiness. Her marriage is loving and stable. He brings her lunch at work; she supports his dreams of painting.

Marge’s scene with Mike is our first glimpse at how difficult it is for her to comprehend the malevolence of some people. He lied to her for no reason, and that baffles her.

Of course, Mike’s lie is nothing compared to the evil that lurks at the heart of the story. Jerry is contemptible, and the two men he pays to kidnap his wife are heartless and cruel. They respond to violence with violence, leaving a wake of death everywhere they go.

“I just don’t understand it,” Marge says, and in doing so she reminds us that just as there are bad people in the world who do bad things, there will always be good people to counteract them.

It struck me that all three of these movies featured a single line that “unlocked” the main theme.

Does that mean that a good movie must have a clean one-line explainer?

Of course not.

But the presence of a clear theme gives the writer a compass of sorts. Every character, scene, or action functions in service of the theme to prove whatever argument the film puts forth.

Focused writing, in turn, often produces good writing.

Additionally, the more focused the theme, the more succinctly one can express it. A verbose thesis does not indicate a profound one—it only suggests that the writer did not understand their point well enough to put it concisely.

Therefore, if your script has a strong theme that you understand deeply, you will likely be able to communicate it with a single sentence.

And if, by chance, that sentence would find its way into the dialogue of your movie…

Why, you just might have written a good film.