Striking a Chord: Andrew Lloyd Weber's Perfect Ending

How music tells a story (and why the Phantom chord is so dang good).

Happy Thursday, reader. Good to be back.

You may be wondering what caused the hiatus between this and my previous newsletter. The answer is quite simple: I, like Shohei Ohtani and the Outback Steakhouse Bloomin’ Onion, am a starter.

Volumes and volumes of in-progress works haunt every corner of my computer’s hard drive, from infant songs to half-finished prologues to, yes, even barely-begun newsletters.

To me, starting is easy; finishing’s harder.

See, endings are crucial. Just look at Game of Thrones: a show which should be easily considered one of the greatest of all time can instead only carry that title alongside an asterisk thanks to its questionable final season. A good (or bad) ending entirely reframes the way we experience something.

Of course, we aren’t here to tackle narrative resolutions, as that topic has already been addressed in this newsletter’s inaugural post. Rather, we’ll shift our attention from the screen to the stage and, after a bit of background, explore how Andrew Lloyd Weber wrote one of the most climactic resolutions of all time in his 1986 musical The Phantom of the Opera.

I. The Beginning of the End

Before we launch in Phantom, we need to get some background on how composers traditionally end songs. It seems a simple question, but to answer it completely would require a more-than-trivial amount of music theory (which I have happened to write in the appendix).

Instead of getting into all of that here, let’s go with this: typically, songs comprise a melody played over chords. The melody is the tune that gets stuck in your head, and the chords are the supportive backdrop for that tune.

Chords can completely reframe a melody. The same tune over different chords will take on a starkly different feeling. But that is another story and shall be told another time.

The key thing here is that when composers (and when I say composers I am referring any songwriter, past or present) want to end their song/piece, they need to choose the right chords that will create a satisfying resolution.

That resolution is called a cadence.

Chords are the words. Cadences are the punctation.

There different kinds of cadences; I’ll briefly explain three relevant ones below.

1. The Authentic Cadence

One type of cadence is an authentic cadence. It is so named because it feels real, strong, and final. Composers have used it for centuries to end their pieces. If you feel a strong sense of resolution at the end of a song, it almost certainly used an authentic cadence.

The authentic cadence is like a period (or sometimes even an exclamation mark). It is final and conclusive. But we need more punctuation than just a period. We need…

2. The Half Cadence

A half cadence is like a breath, a pause, or…a comma. It’s often used to break up phrases, like in “Mary Had a Little Lamb.” Hum the melody out loud to yourself—listen how the first half ends slightly suspended (“Mary had a little lamb, little lamb, little lamb…”), and then the second half resolves really nicely (“…whose fleece was white as snow”). That’s a half cadence followed by an authentic cadence.

3. The Deceptive Cadence

The cheeky one. The sneaky one. The deceptive one.

You see, a deceptive cadence is almost identical to an authentic cadence, except you switch out one note in the final chord. The result is surprising but satisfying, like a lasagna that you didn’t order.

There is a lot more to these resolutions than I have written here. A truckload more. Fortunately, I have appended an appendix (A. Curtain Call) to this newsletter that will give you a much better understanding of why these cadences exist, if you’re interested in such a thing.

But for now, we can move on to

II. The Main Event

The Phantom of the Opera is a musical that debuted in London’s West End in 1986. Most people would say it’s by Andrew Lloyd Weber, who wrote the music, but we should also extend credit to lyricists Charles Hart and Richard Stilgoe. It’s based on a 1910 French novel of the same name.

At the core of the musical is a love triangle. The key players:

Christine Daaé, an opera singer with moderate-to-severe daddy issues,

Raoul, a nice guy who knew Christine when they were kids (cue the unfortunate “my, you’ve grown” trope), and

The Phantom, a renegade bad boy who haunts the local opera house and murders unsuspecting custodians.

Needless to say, the story writes itself.

Now, I’m going to direct you to specific moments throughout the musical, but for full effect and proper appreciation I recommend you watch the performance. You can rent it on Amazon here for $4.29. Why, that’s less than a cup of coffee!

In the event that you don’t want to interrupt your reading of this newsletter for a 2.5 hour foray into the utterly macabre world of Weber’s Phantom, I direct you to this Spotify album, which is a recording of the entire performance.

Just make sure you’re listening to the 25th anniversary version. It’s better than the others, and I’ll direct you to specific timestamps from this version.

And with that, the lights turn low and the crowd grows quiet. Let the journey begin.

Overture (0:00 – 2:15)

We’ve traveled back in time to an opera house in the year 1881. There’s a big fancy chandelier overhead.

Most musicals (and most movies, and some albums) start with an overture, which is a medley of a significant themes that will pop up throughout the work. It’s an appetizer—a way to plant some important melodies in our mind so we’ll recognize them when they come back later.

Phantom’s overture is no different. Listen up to 2:15 (when the music cuts out and the opera starts). You’ll notice some things:

The Chord. Huge, iconic, disruptive, amazing. It’s a D minor chord, if you’re interested.

The chromatic run. The iconic bum-bum-bum-bum-bummmmm that follows the Chord is taking 5 consecutive notes from the chromatic scale—D to Bb (see the appendix for more on the chromatic scale).

The themes! Enjoy as Weber lays out his sonic landscape.

Think of Me (6:30 – 8:10)

You’ll hear Christine auditioning for a role (kind of) and Raoul noticing her from the audience during a performance of that role.

This is Weber giving us his take on the conventional opera song. Among other things that I won’t get into now, this song ends on a huge authentic cadence, strengthened by Christine’s vocal embellishments. It’s a perfect, traditional resolution for a traditional song. Love it.

Phantom of the Opera (0:00 – 4:15)

The Phantom has been teaching Christine to sing ever since her dad died, and when Raoul asks her out the Phantom gets jealous and takes her down to his lair. Then he sings to her about how much power he has over her.

I’m including this because I’m trying to give you the bare minimum you need to understand the musical, and this is basically the “single” from the whole thing. This is the one people know. So you should know it too.

My favorite part:

Phantom: “In all your fantasies, you always knew / that man and mystery…”

Christine: “…were both in you.”

It’s not just that Christine completes the rhyme—it’s that she had to. If she hadn’t chimed in, he couldn’t have covered by singing “were both in me.” He needed her to finish it, and he knew that she would, because he has so much power over her.

So how does this song end?

It kind of…doesn’t. I had you stop listening at 4:15 because after that there’s a pause and then it feels like we launch into a separate mini-song that bridges to “The Music of the Night.” Does that chord at 4:12 sound like a resolution? Kind of, because the instrumentation changes and the momentum stops, but it certainly doesn’t feel like an authentic cadence.

That’s because this is only a half cadence. It’s like ending a sentence with a comma,

It doesn’t make sense! And yet… it works perfectly.

This, friends, is our first, and certainly not last, example of an unsatisfying cadence for our Phantom. Contrast this with Christine’s authentic cadence at the end of “Think of Me”, and we can begin to consider the essential question: what does the cadence imply about the character?

The Music of the Night (0:00 – 5:50)

This is the Phantom’s “I Want” song.

Almost every musical has a big song where the main character tells the audience what they want out of life. Think “My Shot” from Hamilton, or “Let It Go” from Frozen, or “I Just Can’t Wait to Be King” from The Lion King.

So what does the Phantom want?

“You alone can make my song take flight. / Help me make the music of the night.”

Literally, he wants her to sing his song. Interpreting this on a deeper level will be left as an exercise for the reader.

The point is, he’s filled with hope in this song. Listen to the huge swell from 3:02 – 3:25. Note especially how the actor that plays the Phantom (Ramin Karimloo) is lagging slightly behind the orchestra at times. It seems like he holds the big “BEEEEEEEEE” too long—the orchestra stops a second before he does. Interesting…

While we’re here, we may as well appreciate the lyrics, specifically the way “you long to be” pairs with “you belong to me.”

We get a pretty standard resolution at 4:40—it’s big and hopeful, but not quite the conclusion of the song.

The real ending starts around 5:24. The chords keep shifting out from under us; none of them sound like what we would expect to come next. This ending is beautiful and final and perfect; but certainly not a typical authentic cadence. I don’t even think we can call this a half cadence.

The shifty nature of the chords, the way that the notes blend into each other, the fact that every chord sounds out of place and yet somehow fits in—these are indications that we’re experiencing a series of deceptive cadences in action.

By writing authentic cadences for Christine’s themes while the Phantom resorts to half or deceptive cadences, Weber sonically separates the two leads and offers a glimpse into their differing outlooks: Christine is hopeful and trusting (strong, obvious conclusions) while the Phantom is distrusting and sneaky (unclear, vague endings).

Notes (9:20-10:20)

The Phantom leaves a bunch of demands for the opera house, the chief of which is that Christine needs to be the new leading lady. No one really wants this to happen, and no one really cares what the Phantom thinks, so they decide to call his bluff.

Here’s Weber doing a classic opera song again—with some twists, of course. Note especially how right before 9:55 we’re gearing up for a huge authentic cadence, but the resolution is foiled by the Phantom’s theme.

That bum-bum-bum-bum-bummmmmm comes in hot and makes what should have been the end of the song into a deceptive cadence instead. He’s ruined their moment!

At least, he tried to. Keep listening and you’ll hear that they get their big, cheesy, authentic cadence anyway around 10:10. They refuse to appease the Phantom and let him spoil their fun.

In this case, the Phantom’s deceptive cadence feels threatening, while the authentic cadence creates a sense of ignorance and optimism.

All I Ask of You (full song)

At this point the Phantom has killed a guy (remember when they called his bluff?) and Christine is feeling appropriately flustered. Here comes Raoul with a shoulder to cry on (and…a ring?)

This is just a wonderful song. Listen to how they keep teasing the final cadence. As one of them sings “That’s all I ask of you,” the other picks up with the next verse.

But at the very end, they’re able to really let it go. It’s a huge, authentic cadence.

Weber’s decision to have Raoul join in Christine’s authentic cadence demonstrates that the two are alike; they are both traditional and superficial.

I don’t mean superficial in a bad way here; I just mean that both characters are “authentic”—they are able to exist as they are on the surface level. No one has made them feel the need to hide behind a mask.

All I Ask of You (Reprise) (0:50-end)

Always the sore loser, the Phantom laments Raoul and Christine’s engagement and swears to exact his revenge. Remember the huge chandelier from the opening? Let’s hope no one is standing underneath it.

The big chord at the end is so amazing I can’t even stand it.

Listen how he takes their lovely, pure, authentic cadence and warps it into a deceptive cadence with a fury like the crashing of a thousand waves.

Unlike Raoul, the Phantom cannot end with an authentic cadence; he is too different from Christine and too afraid to accept himself as he is. An authentic cadence would require he to be, himself, authentic.

His chromatic theme comes in too and that glorious chandelier from the opening comes crashing down and the crowd goes wild.

And thus ends Act I.

Intermission. Please feel free to grab a refreshment in the back or use the lavatory.

Entr’Acte (0:00 – 3:00)

Plot: This is basically another overture, but for Act II. It reminds us of some old themes, introduces some new ones, and gets us back in the right mindset.

Nothing specific to talk about here. I encourage you to listen to all of the momentary pauses in the music (find the punctuations!) and then try to guess what kind of cadence is being employed.

Masquerade (3:48 – 5:00)

Everyone’s throwing down at a masquerade ball six months after the chandelier fell. Raoul and Christine have kept their engagement a secret because they’re scared of the Phantom, who crashes the party and demands that the theater put on a performance of his latest opus: an opera called Don Juan.

If you start listening at 3:48, you’ll hear several passes at the “normal” resolution of the melody. They get it in your head, so that at 4:40, the deceptive cadence catches you off guard.

Even if I hadn’t already explained the plot, I bet you could tell what happened at 4:40 just by the music. The Phantom has literally and musically gatecrashed!

The Point of No Return (2:40 – 5:20)

The theater is putting on the Phantom’s opera, in which the main character (Don Juan) wears a hood and gets together with a girl. Christine is playing the girl, and some other guy at the company is playing Don Juan. Or so we think—it turns out the Phantom killed the other guy and is playing Don Juan himself! Oh, that Phantom.

This is a meta moment of the show within the show syncing up with the main plot. You can hear Christine slowly putting together that she’s actually singing with the Phantom, building up to the moment when she cuts the cadence off at 3:58 and pulls off Don Juan’s hood.

They were so close to sharing a cadence—but it’s ruined when Christine reveals the Phantom.

Then there’s a pause, and we hear the gentlest little Phantom Chord. It’s quiet, but hopeful. The Phantom can tell that Christine is undecided, and he tries to use that to his advantage.

He comes in soft and sweet, with the same melody of “All I Ask of You.” He builds confidence—she’s into it!—and he works his way to the big cadence. Maybe this time…

NOOOOOOOO.

Everything goes wrong, as demonstrated sonically by an enormous deceptive cadence. Christine rips off the Phantom’s mask (turns out he’s ugly) as the rest of the theater troupe finds the dead body of the guy who was supposed to be playing Don Juan.

Chaos ensues.

Down Once More (7:35-8:42, 12:34-15:00)

Caught in the act, the Phantom retreats back to his lair, dragging Christine with him. Raoul chases after them, and the two men get into a classic “no, she loves ME” spat. Eventually, Raoul’s head finds itself in a noose (that Phantom is a tricky one) and the Phantom gives Christine a choice: say she loves the Phantom or he’ll kill Raoul. So…she makes out with the Phantom for a sec. Having got what he wanted but realizing it will never be enough, the Phantom releases Raoul, and Raoul and Christine run away…

I had you start listening at 7:35—this is the moment when Christine has to make her decision. The big swell and cadence at 8:13 is the moment she kisses him. This is the Phantom’s dream come true, and the lack of a deceptive cadence at 8:13 is almost jarring to us. For the first and only time, the Phantom and Christine get to share an authentic cadence.

Or do they?

An authentic cadence here would suggest that the Phantom has learned to accept himself and is willing to come out of the shadows. However, we can tell that this isn’t entirely true. He’s surprised by the kiss, but he knows it is empty. Even as they make out, Christine is choosing Raoul over him.

Therefore, it is no surprise when the music cuts out at 8:42 with a half cadence. This is the Phantom’s realization that he’s not going to win this one. He goes over and frees Raoul, who grabs Christine and skedaddles.

Well, almost. Start listening again from 12:34.

Silly Christine forgot her veil in the Phantom’s lair, so she and Raoul pop back in for a quick hello and a tone-deaf reprisal of “All I Ask of You.” As she and Raoul grind salt into the Phantom’s ruptured heart, the Phantom can’t take it anymore. He gives up.

Cue the biggest finish of all big finishes ever. The moment that inspired this newsletter.

13:30-13:40.

Notice how “the music of the night” is sang with the same melody as “all I ask of you.”

Notice how the Phantom slows down. He’s lagging slightly behind the orchestra again, fighting against the inevitable pull of the resolution. It’s like he doesn’t want to let go.

Notice how the orchestra hits the huge crash, the enormous cadence at 13:38, a millisecond before the Phantom reaches his last note. He lets the music get there first and then he lands softly on top of it.

Notice how it’s the most definitive, conclusive, authentic cadence in the whole show, and it belongs to the Phantom.

The Phantom, who has spent the entire musical prolonging songs and avoiding definitive endings with half and deceptive cadences.

The Phantom, who has relinquished his dark and frankly unhealthy pursuit of Christine and at last accepted that he has to move on.

It’s over now, the music of the night.

But alas, even this is not the very end of the show. No, the actual resolution of the entire musical is back to those strange, ethereal, shifty chords that ended, appropriately, “The Music of the Night.”

This provides an ambiguous ending to the music. I read this like the spinning top at the end of Inception: vague, intriguing, but not ultra-significant. That is to say, the return to shifty, deceptive chords does not indicate that the Phantom has rejected his big moment of change. Rather, these chords are meant to 1) bookend the musical and 2) accompany the equally mysterious visual ending to the show.

The rest of the theater troupe finds the Phantom’s lair and storms in with murderous intentions. The Phantom does a magic trick (he puts a blanket over his head and then vanishes), and the crowd is left wondering if he really was a Phantom after all.

Then Andrew Lloyd Weber comes out and basks in applause for 20 minutes.

III. Finale

In a previous newsletter I argued that a good story should function like a pressure cooker for its protagonist. The main character has some flaw, and the story develops in such a way as to continually exploit that flaw until the protagonist is forced to change.

Weber’s music tells us all we need to know about the Phantom and his journey through the pressure cooker. All he wants is an authentic cadence. His flaw, however, is that he’s too ashamed of himself and his appearance to fully embrace a loud, obvious resolution.

As a result, he resorts to half and deceptive cadences. No matter how hard he tries to duet with Christine and match her cadences, the circumstances never work out. Even the one authentic cadence they share at the end is a false one; it is immediately transitions into a half cadence.

The key is that this whole time, the Phantom blames all of his problems on his external appearance. He thinks that’s why Christine won’t get with him.

She puts that excuse to bed in the final song:

This haunted face holds no horror for me now. /

It's in your soul that the true distortion lies.

Youch!

With nothing else to hide behind (literally!) the Phantom is forced to change. This is why he releases Raoul and why he is finally able to hit that authentic cadence at the end. It’s an external sign of his internal change.

This encapsulates one of the most crucial aspects of music, especially in the context of storytelling: its ability to communicate emotion and character. Even without a formal understanding of cadences and resolution, the audience can feel that the Phantom chord is disruptive and unexpected. This affects how they consider and view the character and helps Weber construct a satisfying payoff at the end.

Well, musically satisfying.

I still think Christine made a mistake.

#teamphantom

What follows is the appendix. I forgive you if you don’t want to read it.

A. Curtain Call

How do you end a song? It’s a loaded question, and one that I would like to answer as completely as I can. This means that I will delve into just a bit of music theory. I trust you’ll find it as enthralling as I do.

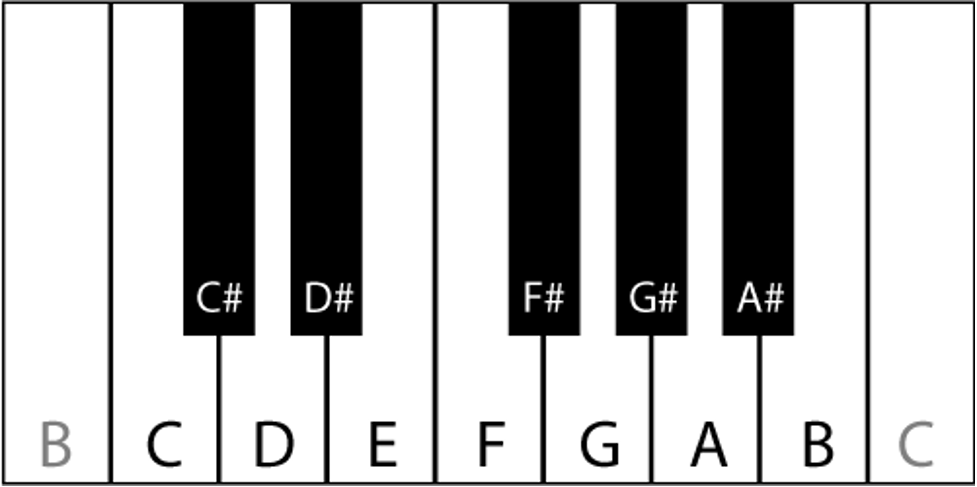

That’s one octave of a piano. Take it in. I want you to notice some things right off the bat:

There are 12 notes. In Western music (which is what I’ve focused on in today’s newsletter), composers typically operate within the bounds of these 12 notes.

There are only 5 black keys. Right you are! There are no black keys between E/F and B/C.

All notes are equally spaced. That is to say, the difference in pitch between two adjacent keys is always the same. The interval (or sonic space) between C and C# is the same as the interval between G and G#, which is the same as the interval between E and F or between B and C or any other two adjacent keys. Crucially, we call this uniform distance a “half-step” or “semitone”. This is an important point; take a second to understand it.

This collection of twelve notes, all one half-step away from each other, is called the chromatic scale. In this case, a scale refers to a group of notes.

The chromatic scale poses a problem to a composer: since all of the notes are equally spaced, they are all equally important (or unimportant, depending on your outlook on life). As mentioned before, we refer to the sonic distance between two notes as the interval between them. The equal intervals of the scale guarantee that all notes are on even footing in the ears of the listener.

This gives a hint at our end destination: if I were to start spamming all of the notes of a piano and then suddenly stopped, there would be no resolution because it didn’t feel like any note mattered more than any of the others. In other words, there is no tonal center.

The Major Scale

The solution to this, as suggested by Pythagoras in ~500 BC, is to create some new scale: a subset of the chromatic scale with unequal intervals between notes. One common subset, at least in Western music, is the major scale. You know the one I’m talking about; if you sing the classic do-re-mi-fa-sol-la-ti-do (think of The Sound of Music), you just sang the major scale.

You can start a major scale on any note you like, but on a piano, the C major scale is particularly easy to visualize: it’s all of the white notes, beginning on C. Feel free to revisit the piano picture to see what I mean. Writing it out here, the C major scale reads:

C D E F G A B (C)

I put that last C in parentheses because the major scale only has seven unique notes; after those seven, the notes just repeat at higher and higher octaves.

Anyway, the important thing about this scale is the unequal intervals. If we use the piano image above, we can sketch out the intervals between all seven notes, where _ denotes a half-step and _ _ denotes a whole-step (equal to two half-steps).

C _ _ D _ _ E _ F _ _ G _ _ A _ _ B _ C

For a different representation, here’s the chromatic scale with the subset of notes comprising the major scale in bold and uppercase:

C c# D d# E F f# G g# A a# B C

As you can see, the distance between C and D is NOT the same as the distance between, say, E and F. Because this scale has uneven intervals, it opens up many sonically interesting possibilities. Namely: chords!

Chords

A chord is a group of three or more notes. Just to recap: one note is a note (:P), two notes form an interval, and three (or more) notes make up a chord.

Technically, that’s the full definition. Three or more notes. Of course, the choice of the notes makes an enormous difference in determining the sound of the chord. Traditionally, composers built chords by taking every other note from a given scale.

For example, in C major, if we take every other note starting with C, we would get C E G B D F… and so on. To keep things simple, we’ll stick with triads, or chords with exactly three notes. Let’s cut our chord down to just C E G.

Musicians would say that this triad is built with a root, a third, and a fifth. This refers to where these notes are relative to each other (not necessarily where they fall in the scale).

Let me explain this a little more. Let’s stick with the C major scale, but build a chord off of D this time.

Well, we start with D. That’s easy enough. That’s our “root”.

One note up from D is E. That would be our “second”, in this case. Let’s skip over it.

The third note is F. We’ll grab it, and aptly call it the “third.”

Now we have D and F. A lovely interval.

Then we skip over the fourth (G) and add A (the fifth) into our chord.

In the context of C Major, we have:

c D e F g A b

In fact, you can build a chord off of every note in the scale. And since the scale has uneven intervals (thanks Pythagoras!), these chords will also have different internal intervals from each other.

For example, let’s take the chord built of C. The interval between C and E, the root and third, is four half-steps (or two whole-steps). Musicians call this interval a major third. Check it out on the piano above.

This is in different from the chord built off of D. The distance between D and F, the root and third, is only three half-steps (since E and F are only a half-step apart). This interval is referred to as a minor third.

So both of these chords have “thirds”, but the type of third is different. Wacky!

The major scale has seven notes, and those notes can be expanded into seven chords. The way the intervals of the scale line up, three of those chords will have major thirds and four will have minor thirds.

Major and Minor Chords

Generally speaking, a chord with a major third is called a “major chord”. A chord with a minor third is called a “minor chord”.

The major chords in the C major scale are built off of C, F, and G. I’ve already shown why C is major, so feel free to check me by counting the half-steps between the root and the third of F and G chords.

The minor chords are built off of D, E, A, and kind of B (the B chord is a slightly different case that we won’t get into now).

We’ll refer to the chords using the roman numeral of their root note, capitalized if the chord is major and lowercase if minor. That is to say, the C chord (which we now know to be major), would be denoted with I, because it is the first (or “one”) chord of the scale. D minor would be ii (“two”). E minor is iii, F major is IV, G major is V, and A minor is vi. For now, let’s just say the chord built off of B is vii, even though that’s not entirely correct.

So we can expand our original scale to represent a chord scale, given by:

I ii iii IV V vi vii

In this chord scale, the I chord is considered important. It’s our home base; we’ll start there and usually return there throughout a given piece. The musical term for idea this is the song’s key. In this case, we are in the key of C major.

The Leading Tone

There’s one more topic we need to address before we move on: the leading tone. The leading tone is what musicians call the note that is one half-step BELOW the root note of the key. In the case of C major, the leading tone is B, because B is one half-step below C. If we were in G major instead, the leading tone would be F#.

Hum do-re-mi-fa-sol-la-tiiiii to yourself, and hold on ti for a second before moving on to the final note. Can you feel it dragging you up to the next do? It’s leading to the resolution of the scale.

Cadences

With the power of music theory behind us, we can now better understand the cadences that I discussed throughout my analysis of Phantom.

1. Authentic Cadence

Q: Why is an authentic cadence so conclusive?

A: The leading tone!

You see, the authentic cadence is the transition of the V chord to the I chord. We sometimes refer to it as a V-I cadence.

If you were to spell out the notes of a V chord, you would notice that the leading tone of the scale is in there (acting as the third of the chord). We know that the leading tone wants to pull us up to the first note of the scale, which means that a V chord resolves very nicely into the I.

That’s why this is such a strong resolution—it’s the pull of the leading tone up to the root.

2. Half Cadence

Q: Why does a half cadence feel like a comma?

A: Because it starts on a V chord…and stays there.

A half cadence occurs when a song or piece works its way to a V chord and then doesn’t resolve to another chord. That’s why we get the floaty feeling of stasis—we know the V should lead to the I (we can practically hear the leading tone pushing up), but it doesn’t happen.

3. Deceptive cadence

Q: Why does a deceptive cadence sound…deceptive?

A: Because it starts with a V chord, but instead of resolving to the I, it goes to a different chord—usually the vi.

Huh?

The vi?

That’s right. Let’s assume we’re working with the C major scale. The I chord, as you know, is made of the notes C E G. The vi chord, built off of A, has the notes A C E. Do you see what’s going on?

They’re really close to each other. Both chords share C and E—the only difference is the whole-step between G and A.

So we have the leading tone that’s present in the V chord still leading to the root of the scale (the B still pushes us to C), but instead of that C being the root of the chord (as in the V-I authentic resolution), the C is now the third of an A minor chord. Fascinating!

That’s all for the appendix folks. Thanks for sticking around. May you never hear a pause in a song without identifying the cadence again.

Until next time.