Do Be Dramatic: Getting the Most out of Your Music

Why the greatest musicians of all time are all drama queens at heart

Ask any two year old and they’ll tell you that if you want to be noticed, you need to be dramatic. “Please” and “thank you” can only go so far; sometimes, you have to kick, scream, and cry your way into the spotlight.

Musicians will tell you the same thing. In a very limited amount of time, they need to grab, hold, and earn your attention. They kick, scream, and cry in their own ways, depending on the situation. Maybe they start really quiet and then crescendo super loud; maybe they only use some instruments at the start and then unleash the full orchestra later; maybe they hold off the most dramatic part of the story for the end of the song.

Whatever the case may be, composers throughout history have arrived at one clear fact: if you want to hold the audience’s attention, you have to be dramatic. More dramatic than you think, probably.

Today, we’re going to look at how different composers and musicians approach this topic. We’ll break down classical music, film music, and contemporary music and see how all of these artists are, in their own way, drama queens.

Fair warning: this is a long one. Especially if you take the time to listen to the examples (maybe skip to the end of the symphony), this is probably a multiple-sitting kind of newsletter.

But hey, at least we’re finally getting another post about music.

THE CLASSICS

Let’s start by breaking down some classical music and seeing how the composers manage to create enormous climactic moments.

1. Béla Bartók’s Music for Strings, Percussion, and Celesta, Mvt. 1

This piece is a reinterpretation of the fugue, a musical form originating in the late 16th century that takes a main theme, called the “subject,” and layers it over and over on top of itself. It resembles a canon (think Row, Row, Row Your Boat), but while a canon layers the subject in the same key, fugues introduce new subjects with different tonal centers. This makes fugues more complex; they present many interesting puzzles for a composer to work out. Writing a fugue, in many ways, is more an exercise in reason and logical problem solving than straight creativity.

If you’re interested in fugues, Johann Sebastian Bach wrote 24 fugues, one in every single key, in a collection of works called The Well-Tempered Clavier. It’s an iconic work, and he kind of owns the form because of it. Bach is to fugues what Beethoven is to symphonies—more on that in a later newsletter.

Fugues are fun to listen to because they’re (typically) easy to follow. The subject is presented very obviously in the opening of the piece so you can pick it out immediately, and then it’s not too difficult to recognize all of the subsequent entrances of the subject. Bartók’s SPC (as I will abbreviate the work) has a very identifiable subject, which you plainly hear in the first five measures. Subsequent entrances in this work are also easy to spot—the first few notes of the subject are very noticeable.

For future reference, let’s make a note of some characteristics of this opening subject.

Dynamics: pp (pianissimo = really quiet)

Range: A3 – Eb4 (a tritone = not very far)

Instrumentation: 2 Violins (very limited)

Something cool about SPC: it is arranged according to the Golden Ratio (~1.62) and the Fibonacci sequence. The Fibonacci sequence is a series of numbers created by adding the previous number: 1 2 3 5 8 13 21 and so on. (How does this relate to the golden ratio? Dividing a number in the sequence by its predecessor gets closer and closer to the golden ratio the further you go in the sequence.) Without getting too in the weeds, every entrance of the fugue falls (more or less) on the measure of a Fibonacci number. That is to say, the second subject enters on measure 5, the next one on measure 8, then 13, and so on.

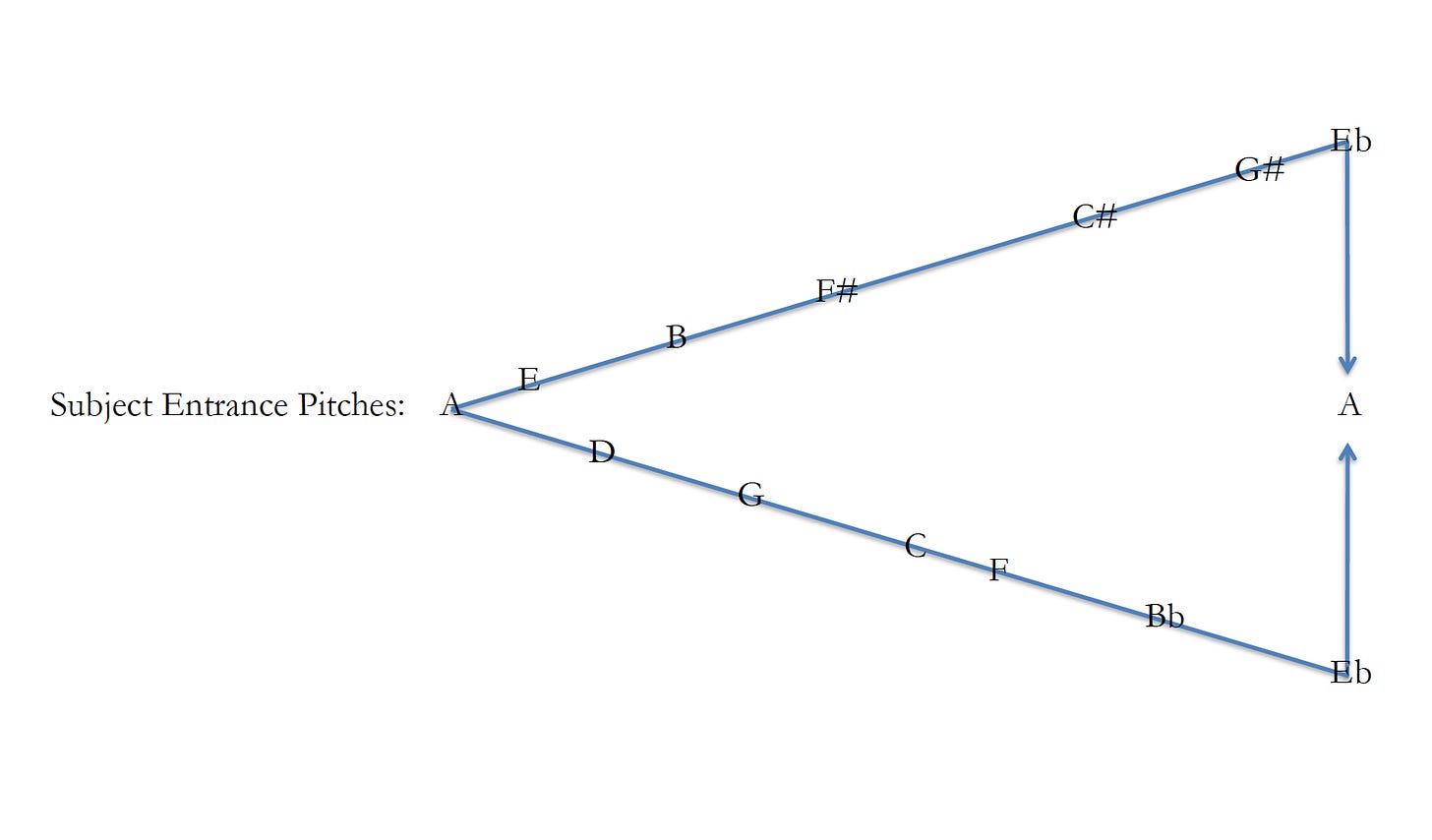

Something else that’s interesting: the subjects enter in very specific keys. The first subject is in A. The next one is a perfect fifth above, entering with a tonal center of E. The third subject enters a perfect fourth below the original A, in D. The fourth subject is a perfect fifth above E, entering in B. The fifth subject comes in a fourth below D, in G. Do you see the pattern? This means that as the piece develops, the range expands dramatically, as shown below.

These two aspects of the piece lead to a dramatic, over-the-top, and amazing climax. Remember how the opening subject only had a range from A up to Eb? Bartók builds the piece more and more, arranging everything according to nature’s “perfect” ratio, until the pattern he’s set up takes him to Eb (not just a note but the tonal center) in both the high and low registers. We love it when smaller themes foreshadow large-scale structure!

So at the climax of the piece, we have:

Dynamics: fff (fortisisimo = really REALLY loud)

Range: Eb1 – Eb6 (5 octaves = really REALLY far)

Instrumentation: 4 Violins, 2 Violas, 2 Cellos, 2 Basses, Bass Drum, Timpani (rich instrumentation)

Measure: 56 (There are 88 measures total. 88/56 ~ 1.6, the Golden Ratio)

This has been a lot on SPC. Here’s a summary of how Bartók sets up a perfect climax:

His opening subject has a range from A to Eb, so he establishes a pattern of subject entrances that will naturally take us from the tonal center A to Eb.

The placement of the entrances according to the Fibonacci sequence implies a huge climax right at the Golden Ratio, measure 56 out of 88.

The dynamic of the opening (pp) leaves lots of room for growth.

The virtuosity of the piece comes from the genius of this set-up and the satisfying pay-off of its natural resolution: hitting a triple-forte, five-octave Eb right at the Golden Measure. It’s masterful writing and beautifully over-dramatic.

2. Tchaikovsky’s everything

For the sake of your time, I won’t do an in-depth breakdown of Tchaikovsky. I just want to point out that the man is a drama queen to the max. Known especially for his ballets, Tchaikovsky excels at writing music with enormously epic climaxes.

Check out The Nutcracker, a lesser-known indie work from 1891. Specifically, listen to the Pas de Deux (Act II, No. 14a; listen here). You’ll hear it build and build and build until a HUGE climax. He actually inserts extra measures and slows down the tempo to add extra tension right before the huge climactic hit (3:31).

This is a hallmark of Tchaikovsky’s music. Just when you thought he couldn’t take the music any higher, he finds a way, damn it, to top it. His fifth symphony (listen here) does the same thing. I saw this performed recently, and the fourth movement is ridiculous. It builds up and up, then cuts back. Then it builds even more, then cuts back. Just when you think it’s going to reach the resolution, it pulls back again. Somehow, Tchaikovsky finds ways to keep building his music. There’s always room to grow, until he reaches the absolute ceiling.

And then he goes even higher.

This is something I struggle with in my own music. It’s easy to feel like you’re going too far when crafting a resolution. But Bartók and Tchaikovsky show that if you want your music to elicit a strong emotional response, you need to turn those mp’s and mf’s into pp’s and fff’s. Don’t be afraid to lean in and wring out every dramatic possibility. You can always take it higher…until you absolutely can’t. Only then are you done writing.

FILM MUSIC

Film scores follow many of the same norms as traditional orchestral music. Specifically, film composers must know when to hold back and when to let the music go to 9000. Let’s look at a couple of famously epic scores and look at how the composers restrain themselves until the proper moment.

1. John Powell’s How to Train Your Dragon

A timeless tale of two unlikely friends, Powell’s score appropriately develops themes for Hiccup and Toothless that begin separate but eventually merge into a climactic moment of sonic glory.

Exhibit A: “This Is Berk” (listen here)

As the first cue of the film, this piece has the responsibility of establishing our main themes while leaving room for those themes to grow and develop. It also occurs over a dramatic fight scene, so it has to be big enough to match the action but not so big that there’s no room for the music to grow. It’s a tough task, but Powell is up for it.

This is our introduction to Hiccup’s two main themes. First, we get Theme A on quiet horns, supplemented by softly swelling strings. The B theme comes in on bagpipes (love it), again understated and subtle, before building up to the main Berk theme, a rousing Viking jaunt. Similar to SPC, this tells us what to expect from the rest of the movie. It’s important to set a clear starting location, so the audience knows exactly what is going to be developed. The more obvious the opening themes, the more satisfying their later resolutions.

You’ll notice that throughout this cue, there are many starts and stops. The music builds, but then cuts back. Powell doesn’t let the piece reach its full potential, because we’re only in the first scene of the movie. He has to leave room for it to grow.

Side note: Listen to 3:55—is that the main subject from SPC?

Exhibit B: “Downed Dragon” (listen here)

We know Hiccup’s themes from the last piece; now, it’s time to introduce their counterparts. In this cue, Toothless’s A theme is subtle and undeveloped. It starts with two big notes (2:56) that echo that two big notes that begin Hiccup’s theme. While Hiccup’s theme ascends from those two notes, Toothless’s descends.

This is crucial because it sets up a way that these two themes could work together in the future. When scoring a film with a large emphasis on themes, composers need to find ways to make those themes work individually and together. It’s a delicate art, akin to crafting a fugal subject that will work on top of itself in different keys. Once again, writing this music is as much about logical problem solving as pure creativity. Sometimes tweaking one note makes all the difference in the world.

Finally, we get a segmented, incomplete version of the Toothless B theme played on bagpipes at the very end of the cue. This quick descending line will come back many times in the score, growing in energy every time. Here, Powell presents the theme so it’s clear enough to recognize, but he purposely leaves it hollow and undeveloped. The full version will come later.

Exhibit C: “Test Flight” (listen here)

If Spotify streams are any indication, this is the most popular track from the score…by a lot. Why? Because it combines the themes of Hiccup and Toothless in an epic, dramatic, and perfect way.

It starts out with fuller versions of the Hiccup and Toothless themes, but they’re still incomplete. They build and build and then cut out—a pattern which should be familiar by now. Powell doesn’t let them reach their full potential, because the characters haven’t reached their full potential. In this way, the music reflects the story.

Then everything goes wrong; the pair starts to fall through the sky. The music loses its structure and rhythm and grows chaotic. The tension builds and builds until…

Toothless B theme! Strong, loud, and nearly complete. But something is still missing; Hiccup and Toothless are flying together, but they aren’t fully in sync yet. Hiccup still relies on his blueprint for instructions.

Until the wind claims his manual, and Hiccup makes a climactic decision. He resigns himself to the dragon. They finally work together.

At this moment, the music goes off the chain. Hiccup’s theme merges seamlessly with Toothless’s theme into a full orchestral moment that proudly and triumphantly blasts both themes. Just as the characters finally work together, their themes do too.

A previous newsletter referred to the concept of the Pressure Cooker, a mechanism by which the plot of a story must constantly put the protagonist in more and more extreme situations. The protagonist has little victories followed by major setbacks. In this way, the tension grows and they are forced to develop as a character.

Good film music treats the themes in the same way. Powell lets the themes grow as the characters grow, and then he undercuts that development in the same way that the story forces the characters into moments of failure. This makes these moments of victory so hugely climactic, because he can finally allow the themes to breathe fully.

2. Hans Zimmer’s The Lion King

Again, I won’t do an in-depth analysis of Hans Zimmer’s score for The Lion King. It is another case of a composer creating themes that seem full in the moment, but still have room to grow. The climactic piece of the film, “King of Pride Rock” (listen here), combines the themes of Simba and Mufasa with the more general motifs for the circle of life and death/rebirth. It all works together to elevate the individual themes into something greater. As the story’s themes all come together in one epic moment, Zimmer pulls out all of the stops to make his music rise higher than it ever has before.

Once again, Zimmer demonstrates that you can always go bigger. The climax of this piece is insanely over-dramatic, arguably way too much. People joke that he didn’t have to go this hard for a children’s movie, but the point is that you do have to go this hard…for every movie. The music of a movie is meant to underscore the emotion of a scene. If you want the scene to feel emotional, the music has to really bring it.

CONTEMPORARY MUSIC

So far, we’ve been looking exclusively at orchestral music; however, these same principles apply to popular music as well. Musicians find different ways to build up their songs and make them overly dramatic as a way to hold the listener’s attention and earn their runtime.

1. Mumford and Sons’ “Dust Bowl Dance”

How does Mumford and Sons leave room for this song to grow? The same way all these orchestral works left room. They start simply and quietly, with just piano and voice. A quick banjo interlude hints at one of the main “themes” from the song—something that will come back in full force later.

Every time that main theme comes back, it’s developed more and more, for example by adding percussion and bass on the second pass. Then electric guitar enters on the third time through.

There’s another technique on display here that we’ve discussed at length: the pull back. The song is one big build, but it does have moments where it cuts back on the energy. This adds tension and allows the song to grow even further. Think of it in terms of energy levels: going from a 9 to a 10 doesn’t seem like that big of a difference, but if you go from a 9 to a 3 and then to a 10, that 10 is really going to hit. In this case, 3:06 is the 9. It seems like that’s the highest energy we can go—cymbals are crashing and the piano is driving the music forward. Then we cut back to a 3, before a plodding drum beat takes us all the way up to the 10.

Except, in a move reminiscent Tchaikovsky, this isn’t the ceiling either. Listen to the drum beat pick up at 3:53. We thought we were at the peak, but they still bring it even higher. The point here is that they could have stopped. They could have kept the song at a 9—but by going to a 10 they drive home the emotion of the song.

It also gives us the opportunity to see Marcus flail around on the drumset like a drunk rag doll.

2. Kendrick Lamar’s “DUCKWORTH”

Let’s check out a different approach to this. Rather than using the music to get more and more dramatic, Kendrick uses the power of language.

“DUCKWORTH” is, in essence, a story. Although the beat varies as the song develops, the main tension and drama comes from the lyrics. Kendrick tells the story of how Anthony “Top Dawg” Tiffith was planning to rob the KFC where Kendrick’s father “Ducky” worked. He explains that Ducky’s generosity caused Top Dawg to spare his life. He concludes with this line:

“Whoever thought the greatest rapper would be from coincidence? /

Because if Anthony killed Ducky, Top Dawg could be servin' life /

While I grew up without a father and die in a gunfight.”

Kendrick’s delivery of this line is crucial. His flow is like a training rolling down the tracks; there’s no interrupting his momentum. The words are falling out of his mouth as he puts a bow on the tale, and ending with “die in a gunfight” hits hard, in part because he chooses to cut the music out from underneath the lyrics. There is another reason this line, and the subsequent gunshot sound effect, has such a strong impact, and it is best articulated by one Michael Scott:

“Think about this, what is the most exciting thing that can happen on TV or in movies, or in real-life? Somebody has a gun. That's why I always start with a gun, because you can't top it. You just can't.”

-Michael Scott, The Office

Needless to say, Kendrick takes the opposite approach. He holds off the most dramatic part of the song until the very ending. He could have included gunshots or more violent imagery during the rest of the song, but if he did so, he wouldn’t have anywhere else to go. By saving this line for the very end of the song, he’s able to do what all of these other examples have done: raise the drama even when it was already through the roof.

Conclusion

We’ve looked at six different examples from three different camps of music, but they all share common characteristics on how they ramp up the drama in order to create a satisfying resolution.

1. Planning

These things don’t happen without significant planning on the part of the artist. Figuring out how to craft your song or piece so that there is room to grow and expand takes a lot of time. Sometimes, musicians start with the final, fully developed theme and then pare down from there. Other times, they purposely craft themes that they know will be able to work together later on.

2. Start/Stop

A great way to ramp up tension without burning out too early is to build the music and then cut it back down. Following the arc of a written story, you can

3. One More Notch

Finally, every single one of these examples goes one step further than you expect. Whether it’s a gunshot at the end of the song, an extra measure of anticipation before the huge payoff, a more energetic drum beat, or whatever the heck is going on in “Test Flight,” all of these artists find a way to take their work to the limit and then push even further. This is what makes these pieces so impactful.

The point is, you can’t be too dramatic when it comes to music (or art in general). In fact, sometimes you have to be more dramatic than you think in order to accomplish the intended effect. So don’t be afraid to turn your energy up to 11 and watch as your pieces become more dynamic, thrilling, and dramatic.

By the way, if you were to listen to every example mentioned in this post, you would hear an hour and sixteen minutes (and eleven seconds) of non-stop melodrama. Thanks for sticking it out.